It all began some time in the early 60’s at New York’s famous club The Village Vanguard. Burt Britton was tending bar, subbing for a friend, and one customer kept asking for more. It was Norman Mailer. Britton tried to shoo him away, but Mailer kept asking for drinks and saying, “What do you want from me kid?” In a flash of inspiration, Britton shoved a napkin Mailer’s way and asked him to draw a self-portrait on it. “That,” says Britton, “was how the madness began.” By the time he published Self-Portrait: Book People Picture Themselves (1976), he had hundreds of these informal portraits from some of the most prominent writers, actors, and artists of our time. I wrote about Self-Portrait in “Self-Portraits of the Artists,” where you can get more of the remarkable story.

It all began some time in the early 60’s at New York’s famous club The Village Vanguard. Burt Britton was tending bar, subbing for a friend, and one customer kept asking for more. It was Norman Mailer. Britton tried to shoo him away, but Mailer kept asking for drinks and saying, “What do you want from me kid?” In a flash of inspiration, Britton shoved a napkin Mailer’s way and asked him to draw a self-portrait on it. “That,” says Britton, “was how the madness began.” By the time he published Self-Portrait: Book People Picture Themselves (1976), he had hundreds of these informal portraits from some of the most prominent writers, actors, and artists of our time. I wrote about Self-Portrait in “Self-Portraits of the Artists,” where you can get more of the remarkable story.

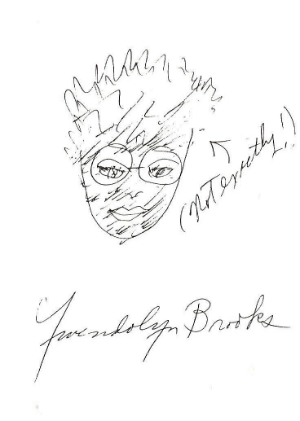

Given the interests of this site, I was delighted to find self-portraits of ten of the black writers I write about here and wanted to show some of these, beginning with Gwendolyn Brooks above. Four of the ones I present here are included in my book Black Writing from Chicago: In the World, Not of It? Go to my articles about them through the links that follow.

Given the interests of this site, I was delighted to find self-portraits of ten of the black writers I write about here and wanted to show some of these, beginning with Gwendolyn Brooks above. Four of the ones I present here are included in my book Black Writing from Chicago: In the World, Not of It? Go to my articles about them through the links that follow.

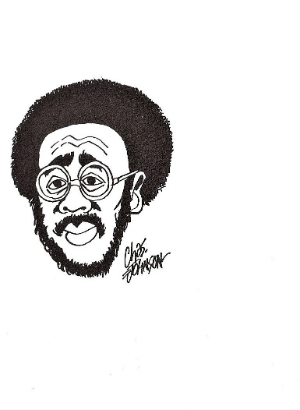

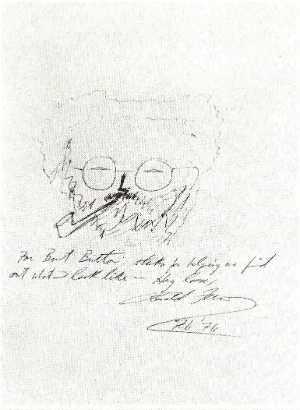

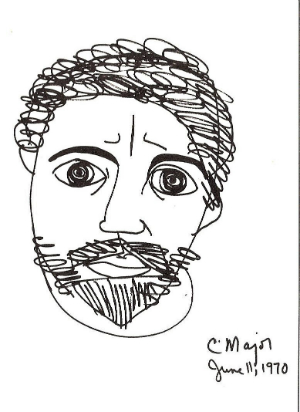

After Gwendolyn Brooks, the self-portraits running down the left side of this post are from Charles Johnson, Ronald L. Fair, and Clarence Major.

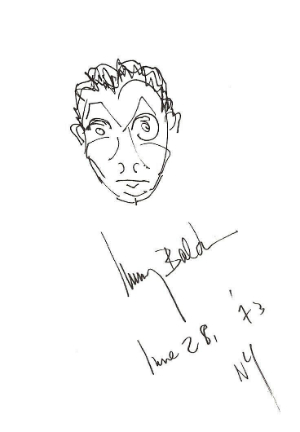

There’s a fifth self-portrait here as well, someone not included in Black Writing from Chicago, but certainly mentioned there and, I think, in most things I’ve ever published. It’s James Baldwin.

There’s a fifth self-portrait here as well, someone not included in Black Writing from Chicago, but certainly mentioned there and, I think, in most things I’ve ever published. It’s James Baldwin.

As I commented in “Self-Portraits of the Artists,” it’s fascinating to see the range of styles: here from the scattering lines of Gwendolyn Brooks’ and Ronald L. Fair’s self-portraits, to the bold starkness of Charles Johnson’s, and Clarence Major’s combination of these two styles. I commented in “Self-Portraits of the Artists” that some of the self-portraits seem contradictory to the writers’ actual styles. My example  was Edward Hoagland’s severely austere drawing style vs. his lush writing style. But all the portraits here seem to fit. Charles Johnson’s “The Education of Mingo,” which I included in Black Writing from Chicago, is certainly bold and boldly etched, as are most of the things he writes. And I find both Gwendolyn Brooks’ drawing and the parenthetical “(Not exactly!)”—complete with little arrow—sweet and self-effacing in the way she often (not always!) presented herself in public. Important for her, too, was the cross-hatching she applied to her face, a move intended to make sure people knew she was black. My introduction to Black Writing from Chicago begins with a quote

was Edward Hoagland’s severely austere drawing style vs. his lush writing style. But all the portraits here seem to fit. Charles Johnson’s “The Education of Mingo,” which I included in Black Writing from Chicago, is certainly bold and boldly etched, as are most of the things he writes. And I find both Gwendolyn Brooks’ drawing and the parenthetical “(Not exactly!)”—complete with little arrow—sweet and self-effacing in the way she often (not always!) presented herself in public. Important for her, too, was the cross-hatching she applied to her face, a move intended to make sure people knew she was black. My introduction to Black Writing from Chicago begins with a quote from Gwendolyn Brooks, a quote intended to justify my calling the book BLACK Writing from Chicago, not African-American Writing from Chicago. Brooks writes: “This objection of mine to the designation African-American is not popular. Nevertheless! The phrase is ISLANDING. The phrase is limiting. The phrase is weak…Almost a honeyed music: AF-ri-can A-Mer-i-can. (As opposed to B-L-A-C-K! Which comes right out to meet you, eye to eye.)”

from Gwendolyn Brooks, a quote intended to justify my calling the book BLACK Writing from Chicago, not African-American Writing from Chicago. Brooks writes: “This objection of mine to the designation African-American is not popular. Nevertheless! The phrase is ISLANDING. The phrase is limiting. The phrase is weak…Almost a honeyed music: AF-ri-can A-Mer-i-can. (As opposed to B-L-A-C-K! Which comes right out to meet you, eye to eye.)”

I find it amazing how well each writer here has captured his or her essence, not just the essence of their styles, but their very looks themselves. All of them, but especially for me James Baldwin.

In “BLACK WRITERS PICTURE THEMSELVES – PART 2,” I show five more self-portraits with links to my writing about them. The five will be Maya Angelou, Ralph Ellison, Leon Forrest, James Alan McPherson, and Toni Morrison.

♦ Go to a list of Black Writers on this site, and to the Teaching Diversity main page.