Burt Britton’s 1976 book Self-Portrait: Book People Picture Themselves contains nearly 750 self-portraits of writers and actors, from Edward Abbey (A) to Paul Zweig (Z). It all started when Britton, then tending bar in New York, tried to get a customer to leave, a customer who wanted drink after drink and kept asking, “What do you want from me, kid?” In a flash of inspiration, the young Britton pushed him a napkin and said, “Draw me a picture of yourself.” The man did. He was a writer. His name was Norman Mailer. So began a life-long habit I tell more about in “Self-Portraits of the Artists.”

I was delighted to find ten self-portraits of black writers that I write about on this site—go Here for the complete list—five of which I presented in “Black Writers Picture Themselves – Part 1.” They were Gwendolyn Brooks, Charles Johnson, James Baldwin, Clarence Major, and Ronald L. Fair. I commented there on the range of styles, “…from the scattering lines of Gwendolyn Brooks’ and Ronald L. Fair’s self-portraits, to

the bold starkness of Charles Johnson’s, and Clarence Major’s combination of these two styles.” I also said they all seemed to capture their peculiar styles and concerns—and their looks, too.

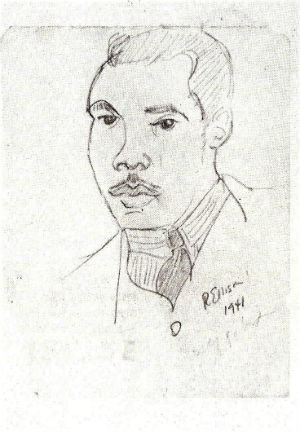

This is Part Two of “Black Writers Picture Themselves,” and in some cases the writers haven’t captured their looks at all. Ralph Ellison did, though. And with a careful realism I find quite moving when you consider the protagonist of his great novel Invisible Man was, well, invisible. What did he look like? What could he look like? It’s as if Ellison’s self-portrait is saying, Look at me. This is what I look like, what the Invisible Man could look like. Not so scary, so monstrous after all.

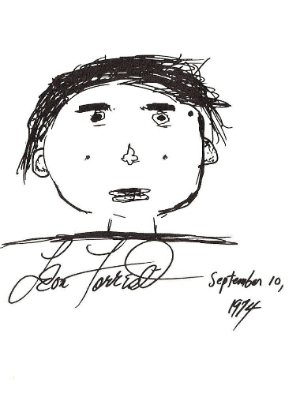

Leon Forrest‘s self-portrait is as far away from scary as you can get. Still touching the realm of realism, his self-portrait, though, seems shot through with a childishness belying the multi-layered complexity of his fiction. His scattering hair perhaps

captures his fiction’s messy-nest thickness, though in real life he was almost always seen with hair slightly slicked back and perfectly coiffed. Which coif James Alan McPherson didn’t have in the slightest! His self-portrait presents a bald primitiveness, almost an anti-drawing, which he explains in his note: “I’d rather write than draw”!

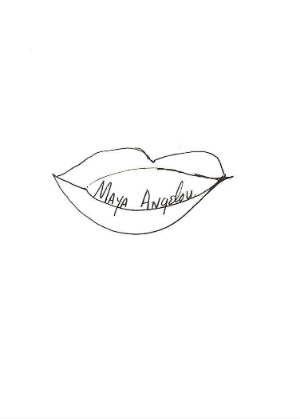

It’s the two women in this second set of five that are the real outliers—at least as far as self-portraits go—and I find it moving that Maya Angelou has chosen to present herself as just a set of lips with her name printed therein. If you ever met her, as I had the great fortune to do, you understand that one of the most memorable things about her was her voice. I suppose, then, that reducing herself to just a pair of lips makes sense. But she was totally memorable—all of her—so it’s a kind of shocking reduction of one of the most memorable people of all time. In “Meeting  Oprah,” a piece which is really about meeting Maya Angelou—whom Oprah calls “Mother”—I speculate on the traumas of her life that made her see herself in a diminished way. Maybe that’s it: the reason her self-portrait is so diminished?

Oprah,” a piece which is really about meeting Maya Angelou—whom Oprah calls “Mother”—I speculate on the traumas of her life that made her see herself in a diminished way. Maybe that’s it: the reason her self-portrait is so diminished?

Which brings us finally to Toni Morrison, where no human form is present at all, not even lips! Morrison pictures herself as a plant, a flower in her flower garden. At first this seems just charmingly self-effacing, until one begins to think about Morrison’s fiction, and her extraordinary literary criticism in “Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination.” I mentioned a kind of primitiveness in James Alan McPherson’s self-portrait, and I suppose there’s some of that here as well. But a flower garden is a different kind of primitiveness than the bald skull McPherson presents. If it’s sweeter, it’s also even more elemental in a way that suggests a kind of pre-human spirit that animates us, certainly, but all life as well. Furthermore, it would be hard  to miss, in Morrison’s fiction, her obsession with shape shifting: of the human form vanishing or flying away (as in Song of Solomon) both as a form of escape and a manifestation of the human having touched some more vital, pre-human spirit. The human doesn’t just escape this way, it also shows up this way (as in Beloved), born in from another world, almost sent back from there to take care of unfinished business. We’re rooted in the here and now, but haunted by unfinished business in other realms of the mind, the spirit, the history and culture of our soil.

to miss, in Morrison’s fiction, her obsession with shape shifting: of the human form vanishing or flying away (as in Song of Solomon) both as a form of escape and a manifestation of the human having touched some more vital, pre-human spirit. The human doesn’t just escape this way, it also shows up this way (as in Beloved), born in from another world, almost sent back from there to take care of unfinished business. We’re rooted in the here and now, but haunted by unfinished business in other realms of the mind, the spirit, the history and culture of our soil.

I believe there may be other black writers in the 750 or so self portraits in Burt Britton’s book, but I’m glad for these ten that add, to my mind, so much dimension to what I have written, or will write, about these writers on this site. All writing is an exercise in portraying yourself, but pictures seem more elemental than words. There’s that old cliche, of course, a cliche that seems more starkly true when writers themselves, so captured by, so entangled in, their nets of words, break free of them for a moment and say in pictures, Here—This, too, is me.