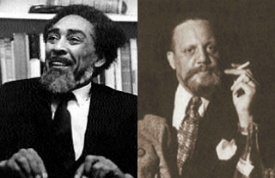

St. Clair Drake (1911-1990) and Horace R. Cayton, Jr. (1903-1970) will forever be bound together for their collaboration on the groundbreaking Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (1945). Drake was born in Suffolk, Virginia, graduated from Hampton Institute and enrolled at the University of Chicago focusing on the sociology and cultural anthropology of black Chicago. He became one of the first black faculty at Roosevelt University, moving to Stanford in 1973 to chair its African American studies program. A prolific lecturer and writer, his other main book was Black Diaspora (1972). Horace R. Cayton was born in Seattle, the son of that city’s pre-eminent black couple, Horace Cayton, Sr. and Susie Revels Cayton. His father, an ex-slave, settled in Seattle in the late 1880’s and published the Seattle Republican. Aimed at both black and white readers, it became the city’s second largest paper. Yet even in the seemingly enlightened northwest, racism proved a decisive factor in housing and labor, and at one point the senior Cayton’s were served an eviction notice for lowering property values in their neighborhood. Horace Cayton, Jr., soon became an activist and staged, among many things, a 1924 one-man sit-in at the segregated Strand Movie Theatre. His association with St. Clair Drake began when he worked under Drake as a researcher for the WPA in Chicago’s Black Belt in the 1930’s. He became deeply involved in Chicago’s writing and art community, numbering Chester Himes and Richard Wright as close friends. Cayton’s other major work was the 1939 Black Workers and the New Unions, and his 1970 autobiography Long Old Road.

Chicago was the site at which so much about the “modern, urban Negro” came to be constructed. Inevitably one thinks of Richard Wright, whose Bigger Thomas, the center of Native Son, a national sensation in 1940, created a mythic kind of Black consciousness defining decades of thinking about Blackness that continues today. In his important essay “Critical Memory and the Black Public Sphere” (in The Black Public Sphere: A Public Culture Book), Houston A. Baker, Jr. writes:

“The scene of modernism for Blacks was to be a Chicago of the intellect and imagination, an urban space in which an archetypal “Bigger” Black consciousness was to find itself caught in a nightmare of acquisitive real estate owners, callous labor leaders, corrupt political officials and morally blind social welfare workers. Bigger in the electric chair might well have been emblematically and realistically enacted by the Black Panthers’ leader, Fred Hampton, who was murdered by the [Chicago] State’s Attorney’s office in 1969.”

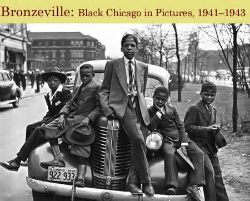

But much of this construction—though perhaps less dramatic—was also done by Drake and Cayton’s Black Metropolis, the first in-depth study of Black urban life. It focused as much on how the community made things work, despite what Baker sketches above. In my book Black Writing from Chicago, I included a small excerpt from Black Metropolis focusing on Bronzeville, Chicago’s “City within a city.” Stretching seven miles from 22nd to 63rd Streets between Wentworth and Cottage Grove, the powerful community of  Bronzeville itself could be said to have led the so-called Chicago Renaissance, a period stretching from 1932 to 1950. Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks and many other writers called it home, of course, but so did Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam, as well as such luminaries as Joe Louis and Mahalia Jackson. Others, like Louis Armstrong, stayed there so often it might as well have been home. Add to this the great publishing enterprises of Johnson Publishing and the Chicago Defender, and it is easy to see Bronzeville supplanting Harlem as the center of Black culture in America—perhaps the world—during the 30’s and 40’s.

Bronzeville itself could be said to have led the so-called Chicago Renaissance, a period stretching from 1932 to 1950. Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks and many other writers called it home, of course, but so did Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam, as well as such luminaries as Joe Louis and Mahalia Jackson. Others, like Louis Armstrong, stayed there so often it might as well have been home. Add to this the great publishing enterprises of Johnson Publishing and the Chicago Defender, and it is easy to see Bronzeville supplanting Harlem as the center of Black culture in America—perhaps the world—during the 30’s and 40’s.

“Black Metropolis has a saying,” Drake and Cayton write: “If you’re trying to find a certain Negro in Chicago, stand on the corner of 47th and South Park long enough and you’re bound to see him.” A monumental study—what anthropologist Clifford Geertz would certainly have dubbed “thick description”—of nearly every conceivable social institution, both “legitimate” and not so above board, and the dynamics that bound them and Bronzeville’s people together, the book was also remarkable in its cultural and psychological insight. “The dominating individual drive in American life is not ‘staying alive,’ nor ‘enjoying life,’ nor ‘praising the Lord,’” they write, “it is ‘getting ahead.’” In large part, this formed the basis of “race pride,” which Drake and Cayton follow as it is “transformed into a positive and aggressive defensive racialism,” where “beating the white man at his own game becomes a powerful motivation for achievement.” As I revisit, expand and post what I wrote and excerpted for Black Writing from Chicago nearly ten years ago, I often wonder how many of the writers I included, but especially Drake and Cayton, would look at Bronzeville today. Now in the mid-teens of the 21st Century, would they still see this community as a power house of Black life? How has it fared under the pressure of the fates of Fred Hampton and others like him; under conditions of the greatest growth of income inequality in American history?

♦ Go to a list of Black Writers.

♦ Go to the Black Writing from Chicago main page, where you can also BUY the book.