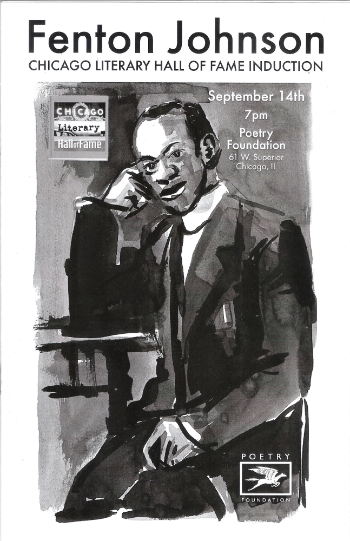

On September 14, 2017, I was asked to be one of the speakers at a ceremony inducting Fenton Johnson into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. Also on the program—co-sponsored by the Poetry Foundation and held at its wonderful John-Ronan-designed headquarters in Chicago—were literary historian Alexander W. Jacobs, poet Vida Cross, and legendary poet-publisher-professor Haki Madhubuti, founder of Third World Press and an architect of the Black Arts Movement. Professor Michele Jolivette, Fenton Johnson’s great grand niece, accepted the CLHoF statue from the Hall’s founder and executive director, novelist Don Evans. Ms. Cross and youth from the Rebirth Poetry Ensemble performed some of Fenton Johnson’s poetry. The following are the gist of my remarks and some afterthoughts as well, which expand upon a previous post, “Fenton Johnson: Request Denied.” Since Johnson did his most famous work in the early 1900’s, and people would probably not be immediately familiar with his work, Don Evans ask me to give a sense of why this poet needed to be honored today.

On September 14, 2017, I was asked to be one of the speakers at a ceremony inducting Fenton Johnson into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. Also on the program—co-sponsored by the Poetry Foundation and held at its wonderful John-Ronan-designed headquarters in Chicago—were literary historian Alexander W. Jacobs, poet Vida Cross, and legendary poet-publisher-professor Haki Madhubuti, founder of Third World Press and an architect of the Black Arts Movement. Professor Michele Jolivette, Fenton Johnson’s great grand niece, accepted the CLHoF statue from the Hall’s founder and executive director, novelist Don Evans. Ms. Cross and youth from the Rebirth Poetry Ensemble performed some of Fenton Johnson’s poetry. The following are the gist of my remarks and some afterthoughts as well, which expand upon a previous post, “Fenton Johnson: Request Denied.” Since Johnson did his most famous work in the early 1900’s, and people would probably not be immediately familiar with his work, Don Evans ask me to give a sense of why this poet needed to be honored today.

_______________

When I think of Fenton Johnson, I think of a poet who played the game so well…until he didn’t.

I mean that he did well what the white world allowed black poets to do. It allowed dialect verse, for example, so Fenton Johnson wrote some of the finest dialect verse ever written with pieces like “Fiddlah Ike” and “Questions,” the latter of which I included in my book Black Writing from Chicago. “Whaih’s de sunlight, Mammy Lou?” it begins, and runs to the sentimental conclusion that the questioner is Mammy Lou’s “wahm sunlight, and his “love’s de moon o’ night.” Black poet’s were also allowed to write sentimental verse not in dialect, but properly formal. So Fenton Johnson wrote that, too, as well as poems related to the “Sorrow Songs,” poems of grieving, religious deliverance, Battle-Hymn-of-the-Republic triumphalism. With “The Vision of Lazarus,” “The New Day,” and “Children of the Sun”—which begins “We are the children of the sun / Rising sun! / Weaving Southern destiny, / Waiting for the mighty hour / When our Shiloh shall appear / With the flaming sword of right”—he also wrote some of the best poems in that genre. For this skill alone, he deserves induction into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.

Don Evans and I congratulating Michele Jolivette, the Poetry Foundation’s magnificent library behind us.

But even more so he deserves this honor because he went far beyond what was allowed. He played the game so well…until he didn’t. To go beyond what was allowed, black poets from the spirituals, through the blues and beyond practiced a lot of signifying, so that the surfaces of their works comforted the gate keepers of decorum, the watchers of what was allowed, but also fooled them, conveying meanings only those in the know would understand. “Steal Away to Jesus” meant, on the surface, getting away to be alone with Jesus—and it meant this sincerely—but it could also signify when the Underground Railroad was coming though so a slave could get on and “steal away” to freedom up North. I’ve tried to catch the signifying undertones of Fenton Johnson’s poetry, but have had a hard time hearing them. When he broke from the game, he broke from it spectacularly with poems like “The Scarlett Woman” and “The Daily Grind” and, most of all, “Tired,” perhaps his most famous poem, which begins: “I am tired of work; I am tired of building up somebody else’s civilization.” It addressed M’Lissy Jane, saying, “Throw the children in the river; civilization has given us too many. It is better to die than it is to grow up and find out that you are colored.”

Such powerfully direct expressions of despair took America by surprise. In his seminal anthology The Book of American Negro Poetry, James Weldon Johnson says that Fenton Johnson’s startling effect on American poetry, “…was in some degree due to the fact that [his poetry expressed] an idea so foreign to any philosophy of life the Negro in America had ever preached or practiced. Fenton Johnson is the only Negro poet who has ever sounded this precise note.” At least, sounded it so directly, so openly, so harshly. Arna Bontemps said Johnson had succumbed “to a more rugged influence.”

I have tried, as I said, to hear a stronger signifying undertone to Johnson’s poetry. How much could he really have meant to “Throw the children in the river,” for example? Is this the same kind of bravura blues singers partook in when they sang, “I’m gonna lay my head down on the railroad track… / When the train comes, I’m gonna snatch it back”? Perhaps. But the blues song finally cops to that false threat, and the music pulses with so much life that we question the threat from the beginning. So while Johnson might not really have meant what he said about the children, and while I try to hear some redeeming “humor” in the name The Last Chance Saloon—where M’Lissy, and the Scarlett Woman, and the poems’ speakers drown their sorrows—there’s nothing pulsing with as much life as the blues, nothing that winks at the threats, thus guiding us clearly to a signifying intent.

I have tried, as I said, to hear a stronger signifying undertone to Johnson’s poetry. How much could he really have meant to “Throw the children in the river,” for example? Is this the same kind of bravura blues singers partook in when they sang, “I’m gonna lay my head down on the railroad track… / When the train comes, I’m gonna snatch it back”? Perhaps. But the blues song finally cops to that false threat, and the music pulses with so much life that we question the threat from the beginning. So while Johnson might not really have meant what he said about the children, and while I try to hear some redeeming “humor” in the name The Last Chance Saloon—where M’Lissy, and the Scarlett Woman, and the poems’ speakers drown their sorrows—there’s nothing pulsing with as much life as the blues, nothing that winks at the threats, thus guiding us clearly to a signifying intent.

In poems like “The Banjo Player” and even “Prelude,” the first poem in his famous 1916 volume Visions of the Dusk, there are strong hints that he knows he’ll get tired of playing the poetry game, that dialect verse and humble peasant stuff was something to break from. When he finally did, he did it in such clear, spectacular fashion, seeding so much of the strong directness in black poetry and culture that would follow. It’s for both his skill at playing the game and his spectacular denial of that game that he deserves our notice tonight and every time we think of great poetry.

♦ Go to a list of Black Writers written about on this site, and to the Teaching Diversity main page.