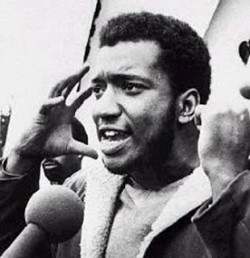

One of the most infamous incidents in Chicago history occurred at 4:45 a.m. December 4, 1969. At that moment Chicago police entered Black Panther headquarters at 2337 West Monroe, starting a one-sided gun battle that killed Panther leaders Mark Clark (1947-1969) and Fred Hampton (1948-1969). Indeed, “assassinated” or “murdered” are now the terms more commonly used, and the picture of the bloody bed where he lay and the bullet-riddled wall behind (at left) has become another icon for state terror against Blacks. 1969 saw eleven Southside youths killed in police skirmishes, a dozen Panthers killed or wounded, and over 100 Panthers arrested—numbers which echo eerily and tragically as I post this over 46 years later. Subsequent research has shown that much of this was under the direction of the FBI, which tracked and harassed Panther leaders and carried out a concerted effort to beat down the Panthers’ “militarily.”

One of the most infamous incidents in Chicago history occurred at 4:45 a.m. December 4, 1969. At that moment Chicago police entered Black Panther headquarters at 2337 West Monroe, starting a one-sided gun battle that killed Panther leaders Mark Clark (1947-1969) and Fred Hampton (1948-1969). Indeed, “assassinated” or “murdered” are now the terms more commonly used, and the picture of the bloody bed where he lay and the bullet-riddled wall behind (at left) has become another icon for state terror against Blacks. 1969 saw eleven Southside youths killed in police skirmishes, a dozen Panthers killed or wounded, and over 100 Panthers arrested—numbers which echo eerily and tragically as I post this over 46 years later. Subsequent research has shown that much of this was under the direction of the FBI, which tracked and harassed Panther leaders and carried out a concerted effort to beat down the Panthers’ “militarily.”

Hampton’s most famous words—“You Can Murder a Liberator, But You Can’t Murder Liberation”—come from his famous speech of the same name, which I excerpted in my book Black Writing from Chicago. In large part, Hampton defends and extols the leaders of the Black Panther Party, Huey P. Newton in particular. “It was Huey P. Newton who taught us how the people learn,” he says. “You learn by participation.” He speaks of Panthers unjustly harassed and jailed, but finally he feels their movement and what it stands for is bigger than any person, leader or not. “So what do we say?” he asks. “Don’t get the pigs offa us cause we can stand em. We jail Mickey White, we should let em murder Bobby Hutton, we should let em run Eldridge Cleaver out of the country. Why? Because you can jail a revolutionary, but you can’t jail the revolution. You can run a freedom fighter around the country but you can’t run freedom fighting around the country. You can murder a liberator, but you can’t murder liberation.”

Hampton’s most famous words—“You Can Murder a Liberator, But You Can’t Murder Liberation”—come from his famous speech of the same name, which I excerpted in my book Black Writing from Chicago. In large part, Hampton defends and extols the leaders of the Black Panther Party, Huey P. Newton in particular. “It was Huey P. Newton who taught us how the people learn,” he says. “You learn by participation.” He speaks of Panthers unjustly harassed and jailed, but finally he feels their movement and what it stands for is bigger than any person, leader or not. “So what do we say?” he asks. “Don’t get the pigs offa us cause we can stand em. We jail Mickey White, we should let em murder Bobby Hutton, we should let em run Eldridge Cleaver out of the country. Why? Because you can jail a revolutionary, but you can’t jail the revolution. You can run a freedom fighter around the country but you can’t run freedom fighting around the country. You can murder a liberator, but you can’t murder liberation.”

Liberation is neither abstract or merely rhetorical because, says Hampton, “…when you’re armed with rhetoric and rhetoric alone a lot of times you get yourself hurt,” or begin to think talk is real action. Among the real actions he’s most proud of is the Breakfast For Children Program. “Our Breakfast for Children program is feeding a lot of chi1dren and the people understand our Breakfast for Children program. We sayin’ something like this—we saying that theory’s cool, but theory with no practice ain’t shit…We have a theory about feeding kids free. What’d we do? We put it into practice. That’s how people learn. A lot of people don’t know how serious the thing is. They think the children we feed ain’t really hungry. I don’t know five year old kids that can act well, but I know that if they not hungry we sure got some actors. We got five year old actors that could take the academy award.”

Five thousand people attended Hampton’s funeral, where he was eulogized by such black leaders as Ralph Abernathy and Jesse Jackson, who said: “…when Fred was shot in Chicago, black people in particular, and decent people in general, bled everywhere.” Hampton’s assassination has been commemorated in much literature, notably in Haki Madhubuti’s “One-Sided Shoot-out,” which ends: “our enemies scope the ways of blackness in three bad / shifts a day. / in the A.M. their music becomes deadlier. / this is a game of dirt. / only blackpeople play it fair.” Hampton, who started as a Youth Council leader for the NAACP before founding and chairing the Illinois Black Panther Party, was known as a restrained, articulate organizer. However, his most central speech, as well as several interviews he gave to Chicago papers in the late 60’s, show that his frustration with obstacles to reform—as well as everyday brutality against Blacks—drove him to accept violence as often necessary, especially for self-defense. In 1990 a “Fred Hampton Day” was declared in Chicago. His son, Fred Hampton, Jr., also gained notoriety as a political prisoner. He was released in September 2001 after nearly ten years in jail and intense protest by the International Campaign to Free Fred Hampton, Jr., and the Democratic Uhuru Movement.

Five thousand people attended Hampton’s funeral, where he was eulogized by such black leaders as Ralph Abernathy and Jesse Jackson, who said: “…when Fred was shot in Chicago, black people in particular, and decent people in general, bled everywhere.” Hampton’s assassination has been commemorated in much literature, notably in Haki Madhubuti’s “One-Sided Shoot-out,” which ends: “our enemies scope the ways of blackness in three bad / shifts a day. / in the A.M. their music becomes deadlier. / this is a game of dirt. / only blackpeople play it fair.” Hampton, who started as a Youth Council leader for the NAACP before founding and chairing the Illinois Black Panther Party, was known as a restrained, articulate organizer. However, his most central speech, as well as several interviews he gave to Chicago papers in the late 60’s, show that his frustration with obstacles to reform—as well as everyday brutality against Blacks—drove him to accept violence as often necessary, especially for self-defense. In 1990 a “Fred Hampton Day” was declared in Chicago. His son, Fred Hampton, Jr., also gained notoriety as a political prisoner. He was released in September 2001 after nearly ten years in jail and intense protest by the International Campaign to Free Fred Hampton, Jr., and the Democratic Uhuru Movement.

♦ Go to the Black Writing from Chicago page, and to a list of Black Writers on this site.

♦ Go to the Teaching Diversity main page.