Note: I have divided my nearly-3500 word introduction to my book Black Writing from Chicago into two parts for this website. Part 1 begins with a quote from Gwendolyn Brooks about her objection to the term “African-American.” It’s my justification for not calling the book “African American Writing from Chicago,” a title some had suggested as more “proper.” Below I explain how Chicago writing fits into the standard literary periods scholars use to talk about Black writing, but I focus most on the character of Black writing that has come from Chicago, and on explaining my rather odd subtitle—a question: “In the World, Not of It?” It ends with a statement about the centrality of Chicago, especially Bronzeville, to Black writing around the world, a theme I detail later. When the book came out one critic noted that at last we had a book that firmly established Chicago as a counterpart of the Harlem Renaissance. I post this Introduction in mid-2015, in the wake of racism’s effects in Ferguson, Long Island, Milwaukee, Cleveland, Baltimore, Charleston, etc. etc. etc. From this perspective, as well as sheer literary merit, it seems to me that Chicago’s Black writing is more relevant today than ever.

Note: I have divided my nearly-3500 word introduction to my book Black Writing from Chicago into two parts for this website. Part 1 begins with a quote from Gwendolyn Brooks about her objection to the term “African-American.” It’s my justification for not calling the book “African American Writing from Chicago,” a title some had suggested as more “proper.” Below I explain how Chicago writing fits into the standard literary periods scholars use to talk about Black writing, but I focus most on the character of Black writing that has come from Chicago, and on explaining my rather odd subtitle—a question: “In the World, Not of It?” It ends with a statement about the centrality of Chicago, especially Bronzeville, to Black writing around the world, a theme I detail later. When the book came out one critic noted that at last we had a book that firmly established Chicago as a counterpart of the Harlem Renaissance. I post this Introduction in mid-2015, in the wake of racism’s effects in Ferguson, Long Island, Milwaukee, Cleveland, Baltimore, Charleston, etc. etc. etc. From this perspective, as well as sheer literary merit, it seems to me that Chicago’s Black writing is more relevant today than ever.

♦ Read PART 2 of the Introduction and go to a list of Black Writers, most of them from this book.

____________________________

This objection of mine to the designation African-American is not popular. Nevertheless! The phrase is ISLANDING. The phrase is limiting. The phrase is weak…Almost a honeyed music: AF-ri-can A-MER-i-can. (As opposed to B-L-A-C-K ! Which comes right out to meet you, eye to eye.) —Gwendolyn Brooks, Report from Part Two

This objection of mine to the designation African-American is not popular. Nevertheless! The phrase is ISLANDING. The phrase is limiting. The phrase is weak…Almost a honeyed music: AF-ri-can A-MER-i-can. (As opposed to B-L-A-C-K ! Which comes right out to meet you, eye to eye.) —Gwendolyn Brooks, Report from Part Two

As might be expected, the writing collected here is sometimes less refined. It’s Chicago writing. Instead, it’s “more.” Describing the daring of the city’s Black writing, Hoyt W. Fuller said it was like Ray Charles’ music: more gritty, more blunt and aggressive, more raw and free-wheeling than most American writing.1 Some of it is more hopeful—Era Bell Thompson’s writing, for example. But Fenton Johnson, one of the city’s earliest literary stars, expressed more despair and more fatalism than any Black writer ever had. He stunned turn-of-the-century America, just as Chicago, the “City of the Century,” stunned America with an explosive growth and grinding materialism which always threatened to crush the human spirit. The arts, too, had to struggle harder, get scrappier, grittier, and when artists survived they expressed more triumph, and sometimes more sentimentality, than elsewhere.

Race added that much more to the struggle. In part, this collection attempts to follow the complex, often clashing, currents of a crucial race theme. My subtitle turns a phrase of Jesus into a question. His followers, he said, were certainly in the world, but were not to be of it, were not to be “worldly.” It has always been a pivotal question for Black Americans: the extent to which they could be, should be, or should want to be part of the world of American culture and society at large. On the one hand, Black culture has contributed in incredible disproportion to what makes the United States so distinctive culturally, politically, spiritually. It has made the U.S. what it is to such an extent that every American could be said to be one-third Black at the very least. Why wouldn’t Blacks want to be integrated into something they have so largely made? Racism blocked this, of course. And it is obvious that American culture has always manipulated Black culture, swallowed it, commodified it, profited from it, while shutting Black people out. Because of this, separatism and integration become opposite poles of a continual spectrum of tension which has played out more powerfully in Chicago than virtually anywhere else.

Rather humble appeals to “play fair” and let Blacks be fully part of America characterize much of the rhetoric of the earliest pieces in this collection, pieces an academic might place in the so-called “Antebellum” period of Black writing in America (1800-1865).2 These give way to more aggressive appeals to reason in the “Reconstruction” period (1865-1900). But after the forging of distinctly Black styles in the “Negro Renaissance” (1900-1940), the “Protest” period (1940-1959) and the “Black Arts Movement” (the 1960’s), Black writing almost obsessively foregrounds the question of assimilation—of how much Blacks should ever want to be part of a larger society that continued to mistreat them. The answer, shouted in Chicago probably louder than anywhere else, was often: Not much, Not in any way if it can be helped. In Chicago from the 60’s to the 80’s, the Organization of Black American Culture, OBAC, was a megaphone for this shout, as well as a major world site for the ferment of Black styles and themes.

In his seminal 1970 essay “The New Black Literature: Protest or Affirmation,” Hoyt W. Fuller wrote: “The trouble with black literature in America is—and always has been—the white literary establishment.” “Even James Baldwin,” he continues, “…bought the assimilationist philosophy and proceeded to launch a brilliant literary attack against the works of Richard Wright in particular and all ‘protest’ literature in general. He lived to regret it.”3 Indeed, shortly after such “assimilationist” attacks, Baldwin began articulating a kind of reverse assimiliation, saying that Blacks needed to forget about integrating with whites. Whites, in fact, needed to integrate into Blackness.4 Ralph Ellison voiced it another way, saying it was time for whites to ask how Black they were, instead of Blacks always having to struggle with being absorbed into whiteness.5 These attempts to see assimiliation in reverse is one of many strategies that map a hazy middle ground between a separatist and an integrationist Black ideology.

In his seminal 1970 essay “The New Black Literature: Protest or Affirmation,” Hoyt W. Fuller wrote: “The trouble with black literature in America is—and always has been—the white literary establishment.” “Even James Baldwin,” he continues, “…bought the assimilationist philosophy and proceeded to launch a brilliant literary attack against the works of Richard Wright in particular and all ‘protest’ literature in general. He lived to regret it.”3 Indeed, shortly after such “assimilationist” attacks, Baldwin began articulating a kind of reverse assimiliation, saying that Blacks needed to forget about integrating with whites. Whites, in fact, needed to integrate into Blackness.4 Ralph Ellison voiced it another way, saying it was time for whites to ask how Black they were, instead of Blacks always having to struggle with being absorbed into whiteness.5 These attempts to see assimiliation in reverse is one of many strategies that map a hazy middle ground between a separatist and an integrationist Black ideology.

Many of the pieces in this collection can be heard talking to each other along this separatist-integrationist spectrum. Some writing focuses on figures who have become icons of that hazy middle ground: Colin Powell, for example—or, more intriguingly, Josephine Baker, who held herself at such a distance from white America even as much of the white world here and elsewhere idolized her. The Intercollegiate Wonder Book can be seen as a handbook for Blacks who want to step fully into American society, while Haki Madhubuti’s Black Men: Obsolete, Single Dangerous? can be seen as a handbook for separatist Blacks, just as his Third World Press championed business, writing, and education by Blacks for Blacks.

Many of the pieces in this collection can be heard talking to each other along this separatist-integrationist spectrum. Some writing focuses on figures who have become icons of that hazy middle ground: Colin Powell, for example—or, more intriguingly, Josephine Baker, who held herself at such a distance from white America even as much of the white world here and elsewhere idolized her. The Intercollegiate Wonder Book can be seen as a handbook for Blacks who want to step fully into American society, while Haki Madhubuti’s Black Men: Obsolete, Single Dangerous? can be seen as a handbook for separatist Blacks, just as his Third World Press championed business, writing, and education by Blacks for Blacks.

The flows across this spectrum are complex. The Chicago Defender newspaper manifested a radicalism that demanded full equality and, perhaps, integration. Yet its habit of referring to African Americans not as “Blacks” or “Negroes” but as “The Race” maintained a strong separatism. In contrast, the writing coming from Chicago’s Johnson Publishing moved clearly towards an integrationist ethic, not only in the way its Negro Digest was styled largely after Readers Digest, or Ebony magazine after Life magazine, but also in its increasing championing of less radical, middleclass values. Yet the content of Negro Digest and Ebony was often very radical, particularly when Hoyt W. Fuller himself worked for Johnson. However, as the excerpt included here makes plain, Fuller’s break with Johnson was largely over the more middleclass direction of Ebony, along with Fuller’s empathy for Palestinians. A clearer case of contrast would be Johnson protégé Era Bell Thompson whose sunny optimism stands in contrast to Richard Wright’s pessimism, just as her American Daughter was deliberately named to stand in contrast to Wright’s Native Son. Yet here, too, Wright cannot be said to be wholly separatist, only hyper-conscious of the difficulties of integration at any level.

It often comes down to attitudes about middleclassness. That theme runs through selections from Sam Greenlee and many others. Hoyt W. Fuller and Ronald L. Fair excoriate the Black middle class while Dempsey J. Travis, Leonidas Berry, and others hold it up. The controversy continually flares, in recent times most famously over Bill Cosby’s May 2004 “lectures” on the problems of Black youth. A 2005 ABC Nightline special on the controversy featured Shelby Steele touting individual responsibility and initiative as the key to full opportunity in American society. But Michael Eric Dyson said it was disingenuous to put the burden so squarely on “the poor.” Not only is the problem more systemic, he said, but the Black middleclass who abandon their brothers and sisters is even more to blame.6 In this book, perhaps the most interesting formulation of the tension occurs when Barack Obama notes a church brochure which says it is all right to seek “middle-incomeness” but not middleclassness. The emotional center of this book, however, is Leanita McClain’s writing. To read her pieces—and Rohan Preston’s poem which alludes to her suicide—is to understand how the question of middleclassness can victimize, how she, like many others, can careen from one end of the integration-separation spectrum to the other.

It often comes down to attitudes about middleclassness. That theme runs through selections from Sam Greenlee and many others. Hoyt W. Fuller and Ronald L. Fair excoriate the Black middle class while Dempsey J. Travis, Leonidas Berry, and others hold it up. The controversy continually flares, in recent times most famously over Bill Cosby’s May 2004 “lectures” on the problems of Black youth. A 2005 ABC Nightline special on the controversy featured Shelby Steele touting individual responsibility and initiative as the key to full opportunity in American society. But Michael Eric Dyson said it was disingenuous to put the burden so squarely on “the poor.” Not only is the problem more systemic, he said, but the Black middleclass who abandon their brothers and sisters is even more to blame.6 In this book, perhaps the most interesting formulation of the tension occurs when Barack Obama notes a church brochure which says it is all right to seek “middle-incomeness” but not middleclassness. The emotional center of this book, however, is Leanita McClain’s writing. To read her pieces—and Rohan Preston’s poem which alludes to her suicide—is to understand how the question of middleclassness can victimize, how she, like many others, can careen from one end of the integration-separation spectrum to the other.

The story by Cyrus Colter shows that the degree to which one embraces the world also depends on the subtleties of personal relationships and the interior landscapes of regret and fear related to, but also beyond, race and class. For Gwendolyn Brooks I chose not more readily available classics like “The Chicago Defender Sends a Reporter to Little Rock,” which would have closely reflected her contributions to the Protest phase of Black writing, but pieces which also show how very personal choices shape our decision to be less “of the world,” as Maud Martha decides. Then again, her wonderful poems to Haki Madhubuti (then Don L. Lee) and Walter Bradford reflect, successively, a delight in a certain kind of “being in the world,” and a determination to “Stay” and not to be beaten down by it. As I have said, the flows across the spectrum of this theme are extraordinarily complex.

So too is the reality of cultural flow which has made Chicago such a central site of Black writing in America, a site flowed to and criss-crossed over and over by thousands of migrants, and by the words, images, spirits, and bodies of the greatest Black artists in the U.S. and the world. Some writers included here, like Charles Johnson and Elizabeth Alexander, have moved on from Chicago. Can we call them Chicago writers? I looked for a certain tone, such as I alluded to in the first paragraph of this introduction, but also for significance of time spent and works published. In Alexander’s case, for example, I included poems from Body of Life, published in Chicago by Tia Chucha press. But the reverse scenario is much, much more the case: why not call more Black writers Chicago writers? Arna Bontemps, Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, Chester Himes, Margaret Walker, Carter G. Woodson, James Alan McPherson, even Harlem’s James Baldwin—it was tempting to claim these and many, many others as “Chicago writers,” so central was the site of Chicago to their careers. For example, Baldwin’s titantic struggle with the father figure brought him to Chicago to seek out Elijah Muhammad, a story he told first in The Fire Next Time; and one of McPherson’s first big writing breaks came when the Atlantic Monthly published his pieces on Chicago’s Blackstone Rangers. For example, perhaps the biggest of them all, Margaret Walker, claimed proudly by Louisiana, wrote For My People, her most famous work and winner of the Yale Younger Poets Prize, while she was with the Federal Writer’s Project in Chicago and participated as a key figure on the Chicago writing scene.

So too is the reality of cultural flow which has made Chicago such a central site of Black writing in America, a site flowed to and criss-crossed over and over by thousands of migrants, and by the words, images, spirits, and bodies of the greatest Black artists in the U.S. and the world. Some writers included here, like Charles Johnson and Elizabeth Alexander, have moved on from Chicago. Can we call them Chicago writers? I looked for a certain tone, such as I alluded to in the first paragraph of this introduction, but also for significance of time spent and works published. In Alexander’s case, for example, I included poems from Body of Life, published in Chicago by Tia Chucha press. But the reverse scenario is much, much more the case: why not call more Black writers Chicago writers? Arna Bontemps, Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, Chester Himes, Margaret Walker, Carter G. Woodson, James Alan McPherson, even Harlem’s James Baldwin—it was tempting to claim these and many, many others as “Chicago writers,” so central was the site of Chicago to their careers. For example, Baldwin’s titantic struggle with the father figure brought him to Chicago to seek out Elijah Muhammad, a story he told first in The Fire Next Time; and one of McPherson’s first big writing breaks came when the Atlantic Monthly published his pieces on Chicago’s Blackstone Rangers. For example, perhaps the biggest of them all, Margaret Walker, claimed proudly by Louisiana, wrote For My People, her most famous work and winner of the Yale Younger Poets Prize, while she was with the Federal Writer’s Project in Chicago and participated as a key figure on the Chicago writing scene.

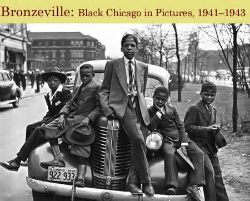

It has become common to acknowledge a Chicago Renaissance (1932 to 1950) flowing across the traditional line between the Negro Renaissance and the Protest Movement mentioned earlier. This renaissance was led by individuals like Richard Wright and Gwendolyn Brooks, but perhaps as much by a powerful community, Bronzeville, a site stretching seven miles from 22nd to 63rd Streets between Wentworth and Cottage Grove. The home of Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam, of Johnson Publishing and the Chicago Defender (initially at least), of Brooks and many other writers, and of such luminaries as Joe Louis and Mahalia Jackson, Bronzeville supplanted Harlem as the center of Black culture in American during the 40’s.

It has become common to acknowledge a Chicago Renaissance (1932 to 1950) flowing across the traditional line between the Negro Renaissance and the Protest Movement mentioned earlier. This renaissance was led by individuals like Richard Wright and Gwendolyn Brooks, but perhaps as much by a powerful community, Bronzeville, a site stretching seven miles from 22nd to 63rd Streets between Wentworth and Cottage Grove. The home of Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam, of Johnson Publishing and the Chicago Defender (initially at least), of Brooks and many other writers, and of such luminaries as Joe Louis and Mahalia Jackson, Bronzeville supplanted Harlem as the center of Black culture in American during the 40’s.

♦ Read PART 2 of the Introduction and go to the Teaching Diversity main page.