In 1981, after a successful career as an M.D. specializing in gastroenterology, Leonidas Berry wrote I Wouldn’t Take Nothing for My Journey Now: Two Centuries of an Afro-American Minister’s Family. The title echoes a famous black spiritual, a testament of faith overcoming formidable odds, but just as important is the subtitle, Berry’s own testament of what that faith also helped preserve: a black family.

In 1981, after a successful career as an M.D. specializing in gastroenterology, Leonidas Berry wrote I Wouldn’t Take Nothing for My Journey Now: Two Centuries of an Afro-American Minister’s Family. The title echoes a famous black spiritual, a testament of faith overcoming formidable odds, but just as important is the subtitle, Berry’s own testament of what that faith also helped preserve: a black family.

I included excerpts of I Wouldn’t Take Nothing for My Journey Now in my 2006 book Black Writing from Chicago. In the introduction to the excerpt I list more of Berry’s accomplishments and also note that his daughter, Judith Berry Griffin, continues her father’s optimism by directing Pathways to College.

“The author has been prompted to tell this story,” writes Berry, “because…he has felt for many years that it is time to tell more stories of single related Black families who have developed and achieved on their own individual economic resources. There has been far too much of a continuous, ‘mass-analysis’ and ‘statistical’ treatment, more often depreciatory, of the ‘total family’ and special ‘racial’ categories of Black American families.”

Broken homes, absent fathers, promiscuous sexuality—these images often dominate society’s views of many black families, especially if they are poor. Such views were bolstered by Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s 1965 The Negro Family in America: The Case for National Action. Focusing on “the deterioration of the Negro family,” Moynihan, perhaps thinking he would gain sympathy and understanding for the “degraded” situation of black families, attempted to explain this “fact” as the consequence of “…a historical process that had its origins [my emphasis] in the enslavement of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Africans.” He contributed just as much to the persistence of a stereotype. But whites weren’t the only ones anxious to embrace such “facts.” E. Franklin Frazier, the great historian, and—by the way—black, wrote: “The crisis accompanying emancipation tended to destroy all traditional ways of thinking…promiscuous sexual relations…became the rule.” Even a writer as astute as Haki Madhubuti might be misunderstood to agree with such views when he writes in Black Men: Obsolete, Single, Dangerous that black men and women are “Not Allowed to Be Lovers.” (This is one of the book’s major headings. But Madhubuti blames such black family dysfunction on black men who adopt white male role models not only of success, but of how to treat women.) At its deepest level, the acceptance and persistence of negative views about black families by most whites and occasionally blacks themselves, fits in so logically, so naturally—as James Baldwin would have said—into a cultural feeling and a national theology equating blackness, and therefore black people, with sin and damnation.

Broken homes, absent fathers, promiscuous sexuality—these images often dominate society’s views of many black families, especially if they are poor. Such views were bolstered by Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s 1965 The Negro Family in America: The Case for National Action. Focusing on “the deterioration of the Negro family,” Moynihan, perhaps thinking he would gain sympathy and understanding for the “degraded” situation of black families, attempted to explain this “fact” as the consequence of “…a historical process that had its origins [my emphasis] in the enslavement of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Africans.” He contributed just as much to the persistence of a stereotype. But whites weren’t the only ones anxious to embrace such “facts.” E. Franklin Frazier, the great historian, and—by the way—black, wrote: “The crisis accompanying emancipation tended to destroy all traditional ways of thinking…promiscuous sexual relations…became the rule.” Even a writer as astute as Haki Madhubuti might be misunderstood to agree with such views when he writes in Black Men: Obsolete, Single, Dangerous that black men and women are “Not Allowed to Be Lovers.” (This is one of the book’s major headings. But Madhubuti blames such black family dysfunction on black men who adopt white male role models not only of success, but of how to treat women.) At its deepest level, the acceptance and persistence of negative views about black families by most whites and occasionally blacks themselves, fits in so logically, so naturally—as James Baldwin would have said—into a cultural feeling and a national theology equating blackness, and therefore black people, with sin and damnation.

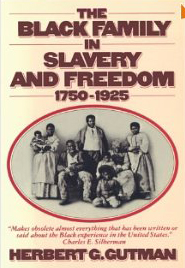

In 1976, Herbert Gutman, a professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, published The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750-1925, synthesizing a view that had been forming for at least a decade, partly in reaction to Moynihan’s extraordinarily influential study. Slavery certainly devastated some aspects of black culture and made stable family life impossible in many cases. The post-Emancipation years were often worse. But blacks also created a vibrant counter-culture. “Of course, slavery was a vicious system,” wrote the great novelist Ralph Ellison, “but, not (and this is important for Negroes to remember for the sake of their own sense of who and what their grandparents were) a state of absolute repression.” Many cultural forms and values survived, among them, Gutman discovers: not just the value of Family Life, but black families themselves. In fact, he asserts that a family unit, even a traditional nuclear family unit, existed in most cases. “Enslavement was harsh and constricted the enslaved. But it did not,” he writes, “destroy their capacity to adapt and sustain the vital familial and kin associations and beliefs that served as the underpinning of a developing African American culture.”

In 1976, Herbert Gutman, a professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, published The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750-1925, synthesizing a view that had been forming for at least a decade, partly in reaction to Moynihan’s extraordinarily influential study. Slavery certainly devastated some aspects of black culture and made stable family life impossible in many cases. The post-Emancipation years were often worse. But blacks also created a vibrant counter-culture. “Of course, slavery was a vicious system,” wrote the great novelist Ralph Ellison, “but, not (and this is important for Negroes to remember for the sake of their own sense of who and what their grandparents were) a state of absolute repression.” Many cultural forms and values survived, among them, Gutman discovers: not just the value of Family Life, but black families themselves. In fact, he asserts that a family unit, even a traditional nuclear family unit, existed in most cases. “Enslavement was harsh and constricted the enslaved. But it did not,” he writes, “destroy their capacity to adapt and sustain the vital familial and kin associations and beliefs that served as the underpinning of a developing African American culture.”

Meticulously researched—ranging from studies of traditional African values to court records showing that nearly 20,000 North Carolina ex-slaves registered their marriages—Gutman’s book makes a compelling case, especially as he counters Moynihan’s emphasis that the absent black male has long been the historical norm in black families. Gutman finds, for example, that in 1925 six of seven black households had two parents.

I wish I knew if Leonidas Berry had read Gutman’s book. In any case, I Wouldn’t Take Nothing for My Journey Now powerfully confirms The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom. Berry tells the story of the Jenifer-Berry-Harris-Jordan family clan, a story of miraculous survival in the face of racist oppression. It’s filled with heroic adventure, like the time members of this clan disassembled their log homes, put them on rafts, ferried them across the Chesapeake Bay, and re-assembled them on farmland where they could be free. “By the first frost in the fall of 1870,” writes Leonidas Berry, “the Berry, Jenifer, Miles and Garner families had completed their crude cabins, and launched out on their undeveloped but independent farm life to rear their children and serve their God.”

Never underestimating the hardships of slavery, but with a refrain emphasizing “cultural progress against formidable odds,” I Wouldn’t Take Nothing for My Journey Now focuses on a “continuous multi-nuclear family unit, across the generations, for two centuries on American soil.” “Since the Civil War,” Berry writes, this family clan has been “of the nuclear variety. That’s to say they have had the presence and support of father as well as mother during the formative and other years of each family unit.” In addition, he stresses the importance of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded by Richard Allen in 1787, and its subsequent founding of Wilberforce University—the first Negro college—in Ohio in 1856. Faith and Education.

Of course, Gutman’s book ends in 1925. In his “African American Families, A Historical Note,” the great American historian John Hope Franklin—also, by the way, black—notes that, “The strong family traditions among blacks survived the slave system, then legal segregation, discrimination, and enforced poverty. Finally black families had to contend with racially hostile governmental and societal practices, policies, and attitudes. These forces ultimately weakened a family fabric that had proved unusually resilient, even in the face of awesome adversity, an adversity that has only grown dramatically since the 70’s.” As I update this post in early 2016, a stunning example of environmental racism—another long, long-standing “tradition”—faces us in the Flint, Michigan, water crisis. And the picture to the left, from the October 2015 cover of The Atlantic, features Ta-Nehisi Coates article on another long-standing, corrosive, growing trend: the mass incarceration of Black men and women that obviously tears families apart. It’s been an increasingly swift downward spiral.

Of course, Gutman’s book ends in 1925. In his “African American Families, A Historical Note,” the great American historian John Hope Franklin—also, by the way, black—notes that, “The strong family traditions among blacks survived the slave system, then legal segregation, discrimination, and enforced poverty. Finally black families had to contend with racially hostile governmental and societal practices, policies, and attitudes. These forces ultimately weakened a family fabric that had proved unusually resilient, even in the face of awesome adversity, an adversity that has only grown dramatically since the 70’s.” As I update this post in early 2016, a stunning example of environmental racism—another long, long-standing “tradition”—faces us in the Flint, Michigan, water crisis. And the picture to the left, from the October 2015 cover of The Atlantic, features Ta-Nehisi Coates article on another long-standing, corrosive, growing trend: the mass incarceration of Black men and women that obviously tears families apart. It’s been an increasingly swift downward spiral.

Still, until the 1960’s, 75% of black families included both husband and wife,” only slightly less than the 78% average of all U.S. families in the late 50’s. 2011 statistics showing that as many as 70% of black children were born “out of wedlock” startle us, though these do not necessarily mean the absence of a father. Furthermore, for well over a decade we have been reading headlines on the decline—the “death” —of the traditional nuclear family across the U.S., the 2010 census showing that only 48% of all U.S. families can now be classified as such.

For black families the point is—the burden of Leonidas Berry’s book is—that whatever the strained state of the black family today, this state is not a historical norm. In fact, the black family has survived two and a half centuries of the harshest life and legal oppression—to which can be added the rape, with little consequence, of tens of thousands of black women by whites. It is important, as Ralph Ellison would say, to know that former generations survived all these.

Leonidas Berry does not claim exclusiveness for his “continuous multi-nuclear family unit.” “Tens of thousands of Black families,” he writes, “have climbed the same mountains to achieve middle-class status [*see note below] and bi-parental relationships. To get there, they have fought the same battles against racial prejudice, unequal opportunities and poverty. The present youngest generation of the Jenifer-Berry-Jordan family shows striking evidence of accelerated cultural growth and exciting prospects for the future of individuals and Black American families….”

____________________

* Black writing from Chicago contains a considerable amount of writing about the difficulties of “middle-classness” for blacks. See especially the excerpts from Barack Obama, Hoyt W. Fuller, and Leanita McClain.

** Go to a list of Black Writers written about on this site, and to the Teaching Diversity main page.