Word comes from Don Evans, founding director of the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame, that Marita Bonner is to be inducted into the CLHOF this November. He said I was the “most knowledgeable” person he knew on the subject, though that’s not saying much. In my book Black Writing from Chicago, I did not include anything from Marita Bonner, though I did write this paragraph in the Afterword, which, more than anything else, is a list of regrets about people I wanted to include but just couldn’t for one reason or another.

“Of Chicago’s many fine short story writers, I would highlight here Marita Bonner, whose work has been collected by Joyce Flynn and daughter Joyce Occomy Stricklin in Frye Street & Environs. Though her vision of the possibilities Chicago offered Blacks had turned quite pessimistic by 1940, her 1926 story “Nothing New” introduced her mythical Frye Street as a vision of the multi-ethnic neighborhood that held hardship, certainly, but also promise. Bonner’s work set tones and themes that deeply influenced writers like Alice Browning and Era Bell Thompson, and echoes of her work can be heard in younger writers like Audrey Petty. Bonner also wrote plays, perhaps most famously the reader’s play The Pot Maker.”

“Of Chicago’s many fine short story writers, I would highlight here Marita Bonner, whose work has been collected by Joyce Flynn and daughter Joyce Occomy Stricklin in Frye Street & Environs. Though her vision of the possibilities Chicago offered Blacks had turned quite pessimistic by 1940, her 1926 story “Nothing New” introduced her mythical Frye Street as a vision of the multi-ethnic neighborhood that held hardship, certainly, but also promise. Bonner’s work set tones and themes that deeply influenced writers like Alice Browning and Era Bell Thompson, and echoes of her work can be heard in younger writers like Audrey Petty. Bonner also wrote plays, perhaps most famously the reader’s play The Pot Maker.”

The title of this article I write here is a riff on a passage from Emily N. Hinnov’s “Manneuvers of Silence and the Task of ‘New Negro’ Womanhood” in the Spring 2012 Journal of Narrative Theory, where she comments on Bonner’s use of silence “as a means to maneuver among the various identity positions that comprise the interstices of ‘New Negro Womanhood.'” Initially, I didn’t include Marita Bonner in Black Writing from Chicago because she is perhaps first identified with the Harlem Renaissance, a period and movement I wanted to challenge a bit in my book. I wanted to show that Chicago Black Writing was as rich, and in many ways more important than the more acknowledged writers from Harlem, an effort writer/scholar Carla Cappetti noted when she said my selections celebrated “the vital traditions of African American writing in Chicago as an important counterpoint to African American Writing in New York and the Harlem Renaissance.”

Yet, while identified with the Harlem Renaissance and the “New Negro” movement, Marita Bonner escaped these identities in all sorts of ways, even geographically. She was born (1899) and went through high school in Boston, then taught in West Virginia before moving to Washington, D.C., where she was an integral part of poet/playwright/composer Georgia Douglas Johnson’s S Street Salon, a major gathering place for writers and artists of the New Negro Renaissance movement. While in D.C. she met William Almy Occomy. Shortly after marrying, the pair moved to Chicago, where her greatest period of writing success occurred, and where she died in 1971.

In her 2008 book Race, Gender, and Comparative Black Modernisms, Jennifer M. Wilks studies four writers, two from the U.S.—Marita Bonner and Dorothy West—and two from the Carribean—Suzanne Lascascade and Suzanne Césaire—as writers who tried continually to escape identities imposed on them by race and gender. Yes, Marita Bonner embraced the New Negro* concept and was part of the Harlem Renaissance, yet seems just as ambivalent about both—even, like me, wanting to de-center Harlem. In her 2009 review of Wilks’ book Patricia Burns writes that Bonner, who resisted the suggestion “that women should fold themselves into the imagined black collective in order to advance black manhood (and, ostensibly, the whole race), neither celebrates intraracial harmony nor excludes interracial community. Wilks portrays Bonner’s work as multiethnic, gender- and class-focused, and experimental—qualities not often associated with the concept of the New Negro. Wilks writes, ‘for subjects whose experiences of race, gender, and class are not found in representations of model modernity, Bonner’s work proposes an alternative modernist cartography, one that ‘removes Harlem from the center of African-American modernity and places multiethnic and multiracial concepts before ‘race’ and ‘nation.’ By depicting communities with ‘multiple boundaries,’ Bonner, Wilks argues, like Lacascade, Césaire, and West, challenges constructions of ‘archetypal blackness’ by interrogating and redefining the tropes of model modernity.”

In her 2008 book Race, Gender, and Comparative Black Modernisms, Jennifer M. Wilks studies four writers, two from the U.S.—Marita Bonner and Dorothy West—and two from the Carribean—Suzanne Lascascade and Suzanne Césaire—as writers who tried continually to escape identities imposed on them by race and gender. Yes, Marita Bonner embraced the New Negro* concept and was part of the Harlem Renaissance, yet seems just as ambivalent about both—even, like me, wanting to de-center Harlem. In her 2009 review of Wilks’ book Patricia Burns writes that Bonner, who resisted the suggestion “that women should fold themselves into the imagined black collective in order to advance black manhood (and, ostensibly, the whole race), neither celebrates intraracial harmony nor excludes interracial community. Wilks portrays Bonner’s work as multiethnic, gender- and class-focused, and experimental—qualities not often associated with the concept of the New Negro. Wilks writes, ‘for subjects whose experiences of race, gender, and class are not found in representations of model modernity, Bonner’s work proposes an alternative modernist cartography, one that ‘removes Harlem from the center of African-American modernity and places multiethnic and multiracial concepts before ‘race’ and ‘nation.’ By depicting communities with ‘multiple boundaries,’ Bonner, Wilks argues, like Lacascade, Césaire, and West, challenges constructions of ‘archetypal blackness’ by interrogating and redefining the tropes of model modernity.”

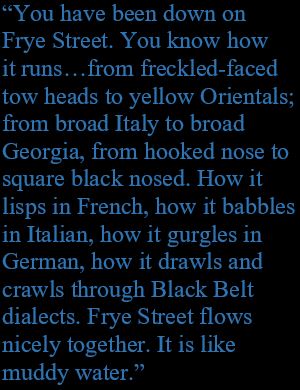

So Marita Bonner turned to multi-ethnicity, to a deep faith in diversity, as ways to escape identities imposed by race, class, and gender. She explored both the possibilities of escape and the continual dangers of entrapment through creating a mythical Chicago neighborhood, Frye Street, which she introduces this way in her story “Nothing New”: “You have been down on Frye Street. You know how it runs…from freckled-faced tow heads to yellow Orientals; from broad Italy to broad Georgia, from hooked nose to square black noses. How it lisps in French, how it babbles in Italian, how it gurgles in German, how it drawls and crawls through Black Belt dialects. Frye Street flows nicely together. It is like muddy water.” The nice flow is still a dream, one glimpsed poorly through very muddied waters.

The Chicago Literary Hall of Fame has made a stunning choice for its 2018 class of inductees, which will include, besides Marita Bonner, Robert S. Abbott (publisher of The Chicago Defender) and fiction writer Henry Blake Fuller. Wanting to keep a Chicago focus, in the paragraph I wrote about her in Black Writing from Chicago, I mentioned how Marita Bonner’s work echoes in Alice Browning, Era Bell Thompson, and Audrey Petty—all writers firmly associated with Chicago. But just as her geography ranged more widely, so does her influence, and I should mention at least one person to whom some have linked her as a fore-mother: Toni Morrison, our country’s most recent Nobel Laureate, an author obsessed with shape shifting, with how races entwine, and with flowing away from the multitude of things—including gender and blackness—that lay in wait to trap us.

* I write about the “New Negro” in my expanded introduction to “The Intercollegiate Wonder Book,” a selection I included in Black Writing from Chicago.

♦ I was privileged to give the Induction Speech for Marita Bonner at Chicago Literary Hall of Fame ceremonies in November 2018. Some of it echoes this article above.

♦ Go to a list of Black Writers on this site.