Actually, though Oprah Winfrey makes a show-stopping appearance in this story, it’s really about meeting the person Oprah calls mother: poet-actress-activist MAYA ANGELOU. I re-posted this by request on the occasion of Maya Angelou’s death in late May, 2014.

Actually, though Oprah Winfrey makes a show-stopping appearance in this story, it’s really about meeting the person Oprah calls mother: poet-actress-activist MAYA ANGELOU. I re-posted this by request on the occasion of Maya Angelou’s death in late May, 2014.

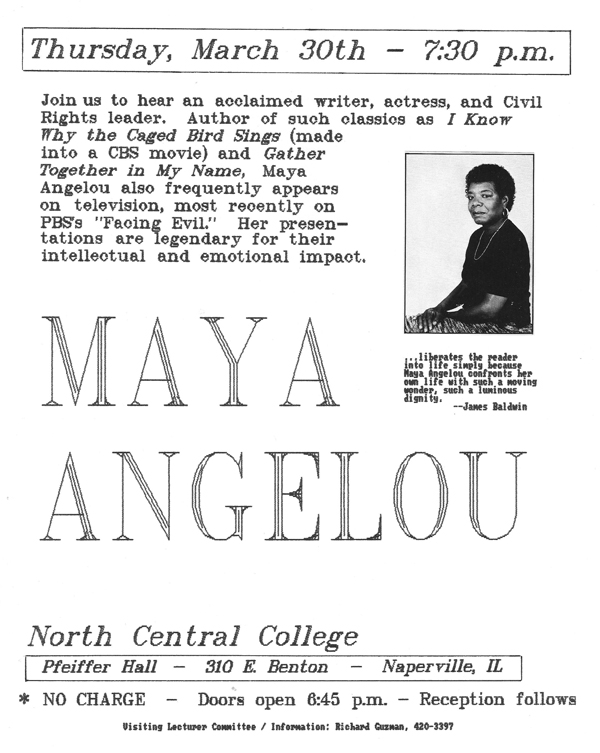

In 1989 I, as director of North Central College’s Cultural Events program, had contracted Maya Angelou to speak on March 6th. On March 1st, however, I got a call from her.

“Richard,” I heard an elegant but obviously distressed voice say, “this is Miss Angelou”—that’s how you addressed her, “Miss Angelou,” or sometimes “Dr. Angelou,” though I don’t recall ever addressing her as “Dr.” then. Maybe “Dr.” was something she took to later, after the weight of all those honorary doctorates began to convince her that we—that is, we Americans—truly did honor her. Then a little less than four years later, on January 20, 1993, she would read her magnificent poem “On the Pulse of Morning,” written for President Clinton’s inauguration, and perhaps all those accolades finally assured her. She is perhaps the strongest, most elegant, most commanding person I have ever met, yet the scars of her upbringing and of racism hurt her so deeply that it took a Presidential inauguration to soothe them enough. Out of that pain she had created her art.

But it was a decidedly more physical pain that had her calling me just days before her scheduled performance. “Richard, this is Miss Angelou. I’m afraid I can’t make it to North Central on March 6th.” My mind raced after it initially blanked. In preparation for her visit I had encouraged as many classes as possible to assign one of her works—any of her volumes of poetry like Just Give Me a Cool Drink of Water ‘fore I Diiie or And Still I Rise, or any of her autobiographical works like Gather Together in My Name, or Singin’ and Swingin’ and Getting Merry Like Christmas, or, of course, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings—and I knew that hundreds of students had been reading them leading up to her arrival late that Winter Term. I might have protested instinctively, though I remember feeling instant shame when she explained that she was in the hospital not only with pneumonia but a broken foot. The earliest she could come was the end of March, the beginning of the Spring Term. I wondered, foolishly, if our audience would disappear.

In fact, there were lines out the door of Pfeiffer Hall, our 1100-seat auditorium, when March 30th came. In the rush of that evening, I remember her saying to me, “Can’t you and I just sit down for a minute. I want to talk with you. Here we are scurrying here and there and can’t take time to just be human. Anyway, you remind me of my son. He’s Filipino, too.” Of course we sat down, though briefly. Back out on stage again to do a mic check, someone handed me a note saying, “Miss Winfrey’s driver has a headache. Do you have anything?” I did. I regularly carried around a couple of packets of aspirin or tylenol on such days, just in case.

A few minutes later that same person—a female student, perhaps on the Pfeiffer Hall staff that day—handed me another note. “Miss Winfrey would like to see the show. Please don’t let things get out of hand.” “Who is this?” I asked. “Miss Winfrey. Oprah Winfrey,” she said, looking at me incredulously.

I hardly knew who she was back then, though I know this is tantamount to admitting that I was born under a rock. I knew her mainly from tabloids I’d scan waiting in line at the grocery, tabloids that seemed inordinately fixated on her weight: “Oprah loses 40,” “Oprah gains 30.” I had watched her show only in very brief snatches and remembered not liking it, though now, like most Americans, I find I have a deep love for Oprah herself, her humanity, her crusading work. But back in 1989, I could only say, feigning familiarity, “Oh, that Miss Winfrey.” I instructed our student to bring Oprah up to the back of the Pfeiffer Hall balcony, sitting her well out of any light, then to bring her down to the Green Room near the end of Miss Angelou’s performance when I gave her the signal.

Miss Angelou’s theme was “You have already been paid for.” Aiming initially at African American students, she reminded us of the horrors of the Middle Passage, of slavery, post-slavery, Civil Rights, of sacrifices unto death, but soon she expanded “You have already been paid for” to us all. For one thing, those black people could be seen to have sacrificed for all Americans, and white immigrants, too, had undergone their trials. How are you going to act, how much will you demand of yourself, how high will you set your sights because you have already been paid for? I broke from the spell of her eloquence and her challenge long enough to signal somewhere up to the dark reaches of the balcony, then left the stage for a moment to greet our surprise guest in the Green Room.

Miss Angelou’s theme was “You have already been paid for.” Aiming initially at African American students, she reminded us of the horrors of the Middle Passage, of slavery, post-slavery, Civil Rights, of sacrifices unto death, but soon she expanded “You have already been paid for” to us all. For one thing, those black people could be seen to have sacrificed for all Americans, and white immigrants, too, had undergone their trials. How are you going to act, how much will you demand of yourself, how high will you set your sights because you have already been paid for? I broke from the spell of her eloquence and her challenge long enough to signal somewhere up to the dark reaches of the balcony, then left the stage for a moment to greet our surprise guest in the Green Room.

What I found was Oprah and another woman I now know was Gayle King, perhaps Oprah’s closest friend. They were beautiful, with long shiney legs and, for Oprah, stunning, electric eyes—green, I think. They were also a bit scolding, irritated, understandably, probably because I had broken them away from Miss Angelou’s spell, the ending crescendo of her performance. I turned away timidly, rushing back on stage to thank Miss Angelou and to announce that she would return in 15 minutes to greet well-wishers and autograph books.

We returned to the Green Room, and Miss Angelou, immediately sensing tension in the air, said to Oprah, “Daughter, don’t be harsh to this man. He was only doing what he thought necessary.” Suddenly, warmth flooded everyone’s demeanor. I am father to many sons, so by chance someone, just days before, had given me a VHS tape they had recorded of an Oprah show on fathers and sons. “I thought it was a remarkable segment,” I said, honestly, but also knowing it was one of the few I had ever seen. “Thank you,” Oprah said, “I thought it was one of the finest things we’d ever done.” Internally, I exhaled a long sigh of relief. I felt sweat break out on my forehead. Saved, again, from looking like a total idiot in front of an icon I barely knew of back then. It wasn’t quite as bad as a few years earlier when I had had to keep the famous director Frank Capra company and had never heard of him or even one of his landmark films. (You can read that story HERE because I seem to revel in revealing my ignorance.)

But now, after a luminous 15 minutes, it was back out on stage, and here I came, trailing Miss Maya Angelou by the hand, who trailed Miss Oprah Winfrey by hers. Hundreds of people remained, and all of them, gasping in disbelief, seemed to rush the stage as one. But stepping up calmly to mid-stage, Miss Angelou held her right arm straight out, palm up, and stopped the crowd, saying, “Grace. Grace. This is my stage. If you would like to meet me and my daughter, please get in line and come graciously.” The command had come out of a humanity that had borne so much pain, had had to wrestle order from so much chaos, that the people suddenly became orderly, calmed by the power of grace. This is my clearest memory of that day, and one of the signal memories of my life.

♦ Go to a list of Black Writers written about on this site.

♦ Go to another appreciation of Maya Angelou.

♦ Go to the Teaching Diversity main page.