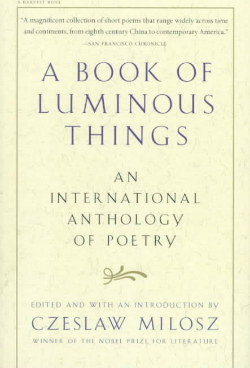

Sometimes I think it’s my favorite book in the world: Czeslaw Milosz’s poetry anthology titled A Book of Luminous Things. Subtitled “An International Anthology of Poetry,” it ranges over continents and centuries giving us mostly short poems from Wang Wei, Charles Simic, Anna Swir, Tadeusz Rozewicz, Steve Kowit, Tu Fu, Rilke, Roethke, Rumi…but nothing from himself, except a translation or two, though he does include a poem from a relative, Oscar V. De L. Milosz. The short bio on the book’s back cover says: “Czeslaw Milosz was born in 1911 in Lithuania. During the Second World War he was active in the Resistance in Poland and later served in the Polish diplomatic corps. A poet, translator, essayist and novelist, he is one of the world’s greatest living men of letters. In 1980 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.”

Sometimes I think it’s my favorite book in the world: Czeslaw Milosz’s poetry anthology titled A Book of Luminous Things. Subtitled “An International Anthology of Poetry,” it ranges over continents and centuries giving us mostly short poems from Wang Wei, Charles Simic, Anna Swir, Tadeusz Rozewicz, Steve Kowit, Tu Fu, Rilke, Roethke, Rumi…but nothing from himself, except a translation or two, though he does include a poem from a relative, Oscar V. De L. Milosz. The short bio on the book’s back cover says: “Czeslaw Milosz was born in 1911 in Lithuania. During the Second World War he was active in the Resistance in Poland and later served in the Polish diplomatic corps. A poet, translator, essayist and novelist, he is one of the world’s greatest living men of letters. In 1980 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.”

This essay is an exercise in humility and just-missed connections.

In 1969 Czeslaw Milosz was apparently in Berkeley, California, thinking hard about the great Indian writer Raja Rao. We presume this because he appends the note “Berkeley, 1969” to the end of this poem of his:

TO RAJA RAO

Raja, I wish I knew

the cause of that malady.

For years I could not accept

the place I was in.

I felt I should be somewhere else.

A city, trees, human voices

lacked the quality of presence.

I would live by the hope of moving on.

Somewhere else there was a city of real presence,

of real trees and voices and friendship and love.

Link, if you wish, my peculiar case

(on the border of schizophrenia)

to the messianic hope

of my civilization.

Ill at ease in the tyranny, ill at ease in the republic,

in the one I longed for freedom, in the other for the end of corruption.

Building in my mind a permanent polis

forever deprived of aimless bustle.

I learned at last to say: this is my home,

here, before the glowing coal of ocean sunsets,

on the shore which faces the shores of your Asia,

in a great republic, moderately corrupt.

Raja, this did not cure me

of my guilt and shame.

A shame of failing to be

what I should have been.

The image of myself

grows gigantic on the wall

and against it

my miserable shadow.

That’s how I came to believe

in Original Sin

which is nothing but the first

victory of the ego.

Tormented by my ego, deluded by it

I give you, as you see, a ready argument.

I hear you saying that liberation is possible

and that Socratic wisdom

is identical with your guru’s.

No, Raja, I must start from what I am.

I am those monsters which visit my dreams

and reveal to me my hidden essence.

If I am sick, there is no proof whatsoever

that man is a healthy creature.

Greece had to lose, her pure consciousness

had to make our agony only more acute.

We needed God loving us in our weakness

and not in the glory of beatitude.

No help, Raja, my part is agony,

struggle, abjection, self-love, and self-hate,

prayer for the Kingdom

and reading Pascal.

Berkeley, 1969

I too wandered Berkeley in 1969, a young undergraduate totally unaware of Milosz’s close presence. A few years later, as a PhD student at the University of Virginia I, too, would stumble upon the writings of Raja Rao and also start thinking hard about him and his words. I would do so even more after I actually met him when, at my invitation and under the auspices of Virginia’s English department, I brought him to Mr. Jefferson’s university—an occasion I will write about in “Car Seats and Destiny: Meeting Raja Rao” (see the second link below). In 1980, the year Milosz received the Nobel Prize, I accomplished an infinitely smaller feat of writing as the Virginia Quarterly, one of the country’s great journals, published my essay “The Saint and the Sage: The Fiction of Raja Rao,” which you can read at the first link below. It’s still considered one of the best essays about Raja, and afterwards talk of a Nobel Prize for him started up again. Raja sent me a book of his short stories, The Policeman and the Rose, shortly after he himself had read it. He inscribed it: “In grateful appreciation of the clear, perceiving mind of Richard Guzman — from Raja Rao.”

Either a short time before or after the article’s appearance, I too published a poem for Raja Rao. It’s called “Neckties,” which you can read Here—or NOT—because here’s where even more humility comes in. I think I’m a good writer, sometimes very good, but of course you get put in your place pretty quickly standing next to Milosz, and fading as you do. My poem tried to capture a moment I had after a night of reading Raja’s novel The Serpent and the Rope. Sometimes his writing transported you so far into mystical realms that you never quite made it all the way back, as I realized I hadn’t when I tried to tie my necktie the next morning. I wanted to capture this confusing moment and realized, too, that I was feeling connections between this moment and situations of imperialism. The poem ends imagining the lack of neckties in traditional Indian dress as a sartorial resistance to imperialism. There’s an allusion to Gandhi’s salt march, and a weird and, I hoped, somewhat funny ending where exclamation points break up sentence flow, emulating the way some imperialist stooge might have tried to bark out orders. It’s a good poem.

Milosz’s poem isn’t one of his best—perhaps especially at the end where he tosses in (or out) Pascal’s name—but it’s still great in the way one of the supreme writers of our time can just toss off a near masterpiece here, another one there. I was trying to capture one moment and link it to some idea about imperialism. Milosz was engaging Raja at one of the deepest levels of difference between himself and his peer, a difference that I knew well. It was the center of my article “The Saint and the Sage.” In this pairing, Raja was the Sage, Milosz the Saint, and Milosz knew he could never be the other. It was at once a difference between two particular writers and two civilizations, “East” and “West,” and Milosz manages to be both personal and grand at the same time.

Milosz’s poem isn’t one of his best—perhaps especially at the end where he tosses in (or out) Pascal’s name—but it’s still great in the way one of the supreme writers of our time can just toss off a near masterpiece here, another one there. I was trying to capture one moment and link it to some idea about imperialism. Milosz was engaging Raja at one of the deepest levels of difference between himself and his peer, a difference that I knew well. It was the center of my article “The Saint and the Sage.” In this pairing, Raja was the Sage, Milosz the Saint, and Milosz knew he could never be the other. It was at once a difference between two particular writers and two civilizations, “East” and “West,” and Milosz manages to be both personal and grand at the same time.

In my article I said the “East” produces “Sages,” those who find peace by traveling inward and towards the realization that the world is illusion. We could say the “East” is obsessed with non-being, or absence—not exactly the same things, but close—while the “West,” as philosopher Jacques Derrida famously told us in “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Human Sciences,” is obsessed with presence. In his poem, Milosz refers directly to presence twice. His line about the “messianic hope / of my civilization” speaks to what I called “the West’s titanic struggle of human personality against the world,” a world perceived both as utterly real—present—and utterly flawed. The West produces “Saints,” moralists who struggle against that imperfection. When they travel inward (even outward) they do not find peace, but a sense of their own, and the world’s, corruption and sinfulness. Rama, the protagonist of Raja Rao’s novel The Serpent and the Rope, says the Westerner “. . . must become saintly, must cultivate humility, because he knows he could be big, great, heroic and personal, an emperor with a statue and a pediment.”

That “pediment” symbolizes the West’s yearning for a solid foundation for presence. Milosz struggles against— is tormented by—“A shame of failing to be / what I should have been,” and his poem begins with him discontent, traveling here and there to find a “city of real presence.” He admits to a kind of schizophrenia and settles for a place only “moderately corrupt.” The Sage, says Rao, “enters into himself and knows he has never gone anywhere. There is nowhere to go….” The Sage finds peace by accepting what is, not chasing what should be. He lets his ego go. “I know the cause of your malady,” I hear Raja saying to his friend. “I know, I know,” Milosz seems to say. “Original Sin,” he admits, “…is nothing but the first victory of the ego. Tormented by my ego, deluded by it, I give you, as you see, a ready argument….” Raja is probably right, he concedes, and does indeed understand his and the West’s malady: the pursuit of a perfect presence, a perfect self and world. In the end, however, he sees no release for himself. “I am,” he says with sad—but also heroic—resignation, “those monsters which visit my dreams.” In this poem two versions of struggling against a sinful, corrupt world face each other. The Saint throws himself against the world. The Sage finally just gives up that world. That’s harder to do than it sounds, even though the world is illusion. It also seems too mystical, but in “The Saint and the Sage” I say, essentially, that “giving up the world” is the fuel that ignites the Indian Revolution. It was an enormously powerful move, very “real”—even practical—in its own way.

♦ Read my “The Saint and the Sage” here, or on the Virginia Quarterly website. In 2002 I traveled to India to give a talk in Kolkatta, which essentially re-read this article, fitting it to India’s problematic rise of Hindu nationalism. I called the talk “Against Pure Purity.”

♦ Go here for more about Raja Rao on this site.