During my long career, I’ve been lucky to meet many writers. Somewhere in the mid-70’s, for example, I met Peter Matthiessen shortly after I’d read his great non-fiction book The Snow Leopard and used it in one of my classes. I had him sign the mass market paperback of his gripping adventure novel At Play in the Fields of the Lord, a novel made into a movie in the early 90’s. I loved his double take when he asked my name, and I said just “Guzman,” the name of one of the book’s notorious characters. After Gwendolyn Brooks, Raja Rao, N.V.M. Gonzalez, and Haki Madhubuti, however, the writer I think of as the most luminous meeting of all is probably Ralph Ellison.

During my long career, I’ve been lucky to meet many writers. Somewhere in the mid-70’s, for example, I met Peter Matthiessen shortly after I’d read his great non-fiction book The Snow Leopard and used it in one of my classes. I had him sign the mass market paperback of his gripping adventure novel At Play in the Fields of the Lord, a novel made into a movie in the early 90’s. I loved his double take when he asked my name, and I said just “Guzman,” the name of one of the book’s notorious characters. After Gwendolyn Brooks, Raja Rao, N.V.M. Gonzalez, and Haki Madhubuti, however, the writer I think of as the most luminous meeting of all is probably Ralph Ellison.

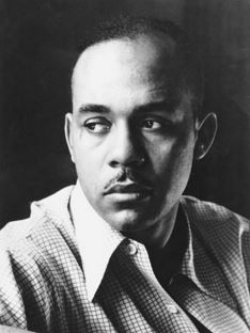

Here, after all, was the author of Invisible Man, a book many have considered the Great American Novel. Again, it was the mid-70’s and I myself was working on my first book, a decidedly smaller project, Voices and Freedoms: A History of Jazz. Ellison, a jazz musician himself, had written a couple of iconic pieces on jazz, and that—not, incredibly, Invisible Man—was what I wanted to talk with him about. In particular, I asked him about a very public feud he’d had with LeRoi Jones (later Imamu Amiri Baraka) after he had reviewed Baraka’s book Blues People in 1963, a book highly touted because it was the first book about jazz written by a black person. Though the feud was some dozen years old, it seemed to me that for Ellison it had happened just last week, such was the irritation that rose in his otherwise calm, sensitive voice and demeanor.

In his review of Blues People—later included in Ellison’s magnificent essay collection Shadow and Act—he accused Baraka of being too ideological, imposing an agenda on jazz and blues that robbed the music of its excitement, and, most of all, a sense of men living in the world—of enslaved and politically weak men imposing their values upon a powerful society through song and dance. Though I love Blues People and still think it one of the most important statements on blues and jazz, one must concede this paradox: it doesn’t always convey a strong sense of what blues and jazz are really like. Also, Ellison says, Baraka often makes rigid distinctions, like between country and classic blues, calling one “folk music” the other “entertainment.” Both kinds can function both ways: it depends on how one wants to use them. Most startlingly, Ellison says Baraka exaggerates the repressive nature of slavery.

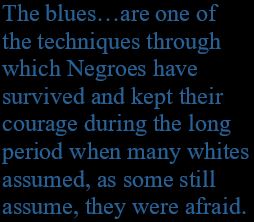

Blacks, said Baraka, could not hope to grow up and be anything but slaves, but Ellison replies that this is too general, that as much as they were slaves, they also saw themselves as jockeys, butlers, farmers, cooks, and they had relationships as males and females, mothers and fathers. Of course, slavery was a vicious system, he says, but “…not (and this is important for Negroes to remember for the sake of their own sense of who and what their grandparents were) a state of absolute repression.” Ellison is adamant. He feels Baraka has missed the art, the aesthetic, of the blues. And it is this aesthetic aspect, rising above the social and political, that made the music a technique of survival. “For the blues,” writes Ellison, “are not primarily concerned with civil rights or obvious political protest; they are an art form and thus a transcendence of those conditions created within the Negro community by the denial of social justice. As such they are one of the techniques through which Negroes have survived and kept their courage during the long period when many whites assumed, as some still assume, they were afraid.”

Blacks, said Baraka, could not hope to grow up and be anything but slaves, but Ellison replies that this is too general, that as much as they were slaves, they also saw themselves as jockeys, butlers, farmers, cooks, and they had relationships as males and females, mothers and fathers. Of course, slavery was a vicious system, he says, but “…not (and this is important for Negroes to remember for the sake of their own sense of who and what their grandparents were) a state of absolute repression.” Ellison is adamant. He feels Baraka has missed the art, the aesthetic, of the blues. And it is this aesthetic aspect, rising above the social and political, that made the music a technique of survival. “For the blues,” writes Ellison, “are not primarily concerned with civil rights or obvious political protest; they are an art form and thus a transcendence of those conditions created within the Negro community by the denial of social justice. As such they are one of the techniques through which Negroes have survived and kept their courage during the long period when many whites assumed, as some still assume, they were afraid.”

This fear is what the Invisible Man transcends, moves around, moves through, during the course of the novel, as he shifts shapes, courting visibility here, invisibility there as situations change. And he’s funny, outrageous. In a recent piece on Leon Forrest, I quote him saying that, after considering some transcendent moments of Gospel Music, he now understands what the old folks were saying: that to make it through this world you need “shit, grit, and mother wit,” things abundant in the Invisible Man’s daily arsenal.

And there’s this aspect of black people actually “living in the world” with each other. In a scathing, deep review of another iconic black work, Richard Wright’s Native Son, James Baldwin says that’s what’s missing about the main character, Bigger Thomas. Because the novel is so ideological, so stuck to the sociological plane, Baldwin says, “…a necessary dimension has been cut away; this dimension being the relationship that Negroes bear to one another, the depth of involvement and unspoken recognition of shared experience which creates a way of life…which has led us all to believe that in Negro life there exists no tradition, no field of manners [to sustain them]…But the fact is not that the Negro has no tradition but that there has as yet arrived no sensibility sufficiently profound and tough to make this tradition articulate.”

Until Ralph Ellison.

The quote above comes from Baldwin’s essay “Many Thousands Gone,” in Notes of a Native Son. In his “Autobiographical Notes,” the first essay of this seminal collection, he says, “…in the advent of Ralph Ellison, one sees the beginnings—at least—of a more genuine penetrating search. Mr. Ellison…is the first Negro novelist I have read to utilize in language, and brilliantly, some of the ambiguity and irony of Negro life.” Now in a world more and more of us realize is still deeply racist, still deeply oppressive of black people, that field of manners, that sense of irony and ambiguity, that sense of blues as survival needs to be invoked more strongly than ever.

♦ Go to a List of Black Writers on this site, and to the Teaching Diversity main page.