In 1905 Robert Abbott began one of the biggest return-on-investment acts of his day: he invested 25 cents to issue 300 copies of his newspaper The Chicago Defender. Eventually this two-cent weekly paper—which he heralded as “The World’s Greatest Weekly”—made Abbott one of the first self-made Black millionaires. It became the most widely circulated Black newspaper in American history. At its height in the 1930’s the paper—bought, passed hand-to-hand, smuggled into the South—is estimated to have had a weekly readership of over 500,000. It was as major a vehicle as our country has ever had for a radical, heads-on attack against the evils of racism.

Robert Sengstacke Abbott (1868-1940) was born on St. Simon’s Island, Georgia, attended Hampton Institute in Virginia, and Chicago’s Kent College of Law, from which he graduated in 1899. Unable to practice law because of race prejudice, he turned to the newspaper trade which he had learned at Hampton and from his step-father. In 1940 Abbott’s nephew John H. Sengstacke took over the paper and continued its championing of full equality. It became the Chicago Defender Daily in 1956, and though its circulation has dwindled and the company has experienced some hard times, its history and influence  remains vital. In fact, it is perhaps impossible to exaggerate the Defender’s influence. Running editorials, cartoons, and train schedules, for example, the Defender helped fuel the Great Northern Migration, which brought over a million Blacks north, over 100,000 of them to Chicago. And though it practiced its own kind of yellow journalism it was a major outlet for some of the most influential Black writers and thinkers in America, including Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, W.E.B. DuBois, Arna Bontemps, Walter White, and many others. Reading a collection of letters between Hughes and Bontemps, it was easy to notice the Defender being mentioned more often than any other site of publishing Its success eclipsed The Broad Ax, The Conservator, and The Illinois Idea, though these other important black Chicago papers deserve mention as well.

remains vital. In fact, it is perhaps impossible to exaggerate the Defender’s influence. Running editorials, cartoons, and train schedules, for example, the Defender helped fuel the Great Northern Migration, which brought over a million Blacks north, over 100,000 of them to Chicago. And though it practiced its own kind of yellow journalism it was a major outlet for some of the most influential Black writers and thinkers in America, including Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, W.E.B. DuBois, Arna Bontemps, Walter White, and many others. Reading a collection of letters between Hughes and Bontemps, it was easy to notice the Defender being mentioned more often than any other site of publishing Its success eclipsed The Broad Ax, The Conservator, and The Illinois Idea, though these other important black Chicago papers deserve mention as well.

In a major review of my book Black Writing from Chicago for Time Out Chicago, Jonathan Messinger spent considerable time on my Chicago Defender selections. He wrote that I had “…included pieces that would otherwise now be inaccessible to contemporary readers.”

“Take, for example,” he continued, “two selections published in the Chicago Defender during the newspaper’s early years. In an editorial from 1917 headlined ‘Keep Your Mouth Shut, Please!’ the editors exhort new residents to keep their voices down on city buses and trains. The editorial reads: ‘Cut this out, dear reader, and whenever you see one talking loudly hand it to them.’ It’s a tasty bit of old-school newspaper belly-aching, but it’s also an extension of the Defender’s leading role as a voice of the ‘Great Black Migration,’ when the paper circulated nationwide and printed train schedules to facilitate the movement of blacks from the South to the North. A few pages later, though separated by nearly 30 years in the paper’s history, Langston Hughes satirizes a similar social problem in one of his popular ‘Simple Stories’ columns, featuring the comic character Jesse B. Semple. Jesse is perturbed at the amount of grease people put in their hair: ‘…there ought to be a law against people with greasy heads going around leaning them up against people’s walls and spotting them all up.’ It’s to Guzman’s credit that he included both of these. Though they seem to address frivolous topics, they also encapsulate the different ways literature can speak to social concerns in the space of the same newspaper.”

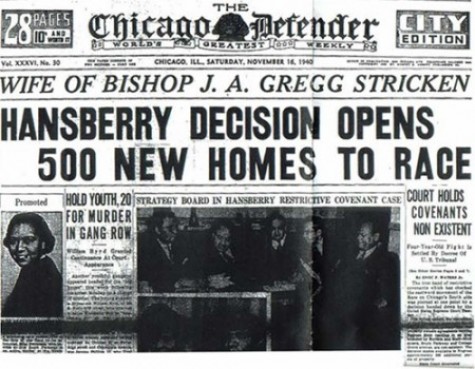

The major theme running through Black Writing from Chicago is expressed in the book’s subtitle. It’s a question, “In the World, Not of It?”—pointing to a historic, long-running debate among black writers and intellectuals: given our nation’s deep, persistent racism, how much could blacks really hope to be a fully integral part of the wider American world? And how much should they want this in the first place? Complex stances and opinions about these questions flowed across a wide, contested spectrum during the Defender’s heyday, and they continue to flow perhaps even more intensely today. The Chicago Defender manifested this complexity and intensity as much as any publication ever has. On the one hand it expressed a radicalism that demanded full equality and, perhaps, integration. Yet its habit of referring to African Americans not as “Blacks” or “Negroes” but as “The Race” maintained a strong separatism.

In 2017, Robert Sengstacke Abbott was elected to the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.

♦ Go to the article “Lorraine Hansberry: The Battle for Fair Housing,” and to a list of Black Writers on this site.

♦ Go to the article “Lorraine Hansberry: The Battle for Fair Housing,” and to a list of Black Writers on this site.