This is Part 2 of a talk I gave in Scottsdale, Arizona, for the Asian Studies Development Programs’ 9th Annual National Conference in 2003. It deals with the efforts of “Third World” writers to develop a “national culture.” READ PART 1, where I introduce and begin analyzing stories from three Filipino writers. Part 1 also identified “magical realism” as the new “international style,” but here we delve further into how an empty center can aid the project of any hybridity, whether the strange blend of magic and realism or something else one fashions, perhaps in the moment, while travelling a world set in dizzying motion by globalization.

The first major statement about the need for Third World writers to develop their own way of expression came in Raja Rao’s 1937 preface to Kantaphura, his groundbreaking novel about the Indian revolution. “English is not really an alien language to us,” he wrote:

“It is the language or our intellectual make-up–like Sanskrit or Persian was before–but not our emotional make-up…We cannot write like the English. We should not. We cannot write only as Indians. We have grown to look at the large world as a part of us. Our method of expression therefore has to be a dialect which will someday prove to be as distinctive and colorful as the Irish or American. Time alone will justify it.

“After language the next problem is that of style. The tempo of Indian life must be infused into our English expression…We, in India, think quickly, and when we move we move quickly. There must be something in the sun of India that makes us rush and tumble and run on…The Mahabharata has 214,788 verses and the Ramayana 48,000…Episode follows episode, and when our thoughts stop our breath stops, and we move on to another thought. This was and still is the ordinary style of our storytelling.”

I believe there is still much merit in exploring the relationship between an author’s individual style and the clarity of his or her conception of their country’s cultural identity. With Chinua Achebe, for example, we find a style tending towards traditional Western realism coupled with the theme of native cultural identity falling apart. In Amos Tutuola, a fellow Nigerian, we certainly see native life falling apart, but his vision of Nigerian and African identity is so solidly based on traditional folk elements that his style itself becomes distinctively African, and a precursor, I might add, to the “international style” I have tried to define above.

Of all Indian writers, I believe Raja Rao most profoundly created a distinctive English, and I believe there is a strong relationship between his stylistic creations and his remarkably strong sense of Indian culture rooted in the Vedas and the concept of Mother India. Over the years I have come to think that while these larger considerations are certainly important, we should also think just as much about the individual writer’s “talent,” what he or she has read, how he or she hears the language, etc., and that this should temper our generalizations about groups of writers. This should be kept in mind as I come towards my conclusion.

I began with the idea that of all Third World writers, Filipinos had the hardest time defining a clearly Filipino cultural identity—so much so that I used the term “empty center,” and traced how increasingly empty that center became through a series of three short stories by prominent Filipino writers. Stylistically, I can say that on the whole, while Filipino writers have produced some of the finest writing in English in the Third World, they also have not produced a writer as distinctively Filipino in style as, say, India has produced in someone like Raja Rao, whose English is profoundly, distinctively Indian.

The one exception to this may be N.V.M. Gonzalez, who, shortly before his recent death, was named a Philippine National Artist. I have wondered a great deal how much his individual ear had to do with his distinctive style, but it also seems like no coincidence that of all Filipino writers, he was most sure of a distinctive Filipino cultural center, one rooted in folk tale, and pre-colonial peasant culture. Nearly 30 years ago I received a letter from him containing the sentence: “I’ve been reading history and a whole ton of it lately, and I can say with some assurance that the Filipino has not changed substantially since circa 1400!”

Gonzalez style contained few of the elements I have described as being part of a so-called new “international style,” but his style was the most distinctively Filipino of any writer I knew. The simple sentences that anchored Bulosan’s style seemed to come as much from Hemingway as from the simple minds of farm laborers like Magno Rubio whom Bulosan often portrayed. Perhaps Ben Santos’ style seemed to fit standard American story-telling style so well because so many of his key stories took place in the United States, but so did many of Gonzalez’s. There is a smoothness and ease of idiom with Santos, however, that is lacking in Gonzalez’s stories, where often, especially when he is trying to use slang, there’s an almost second-language kind of awkwardness. It is this awkwardness that has led me to ask how much is due to the writer’s ear, how he hears the language, and how much to the larger issues of the relationship of writers to some perceived or conceived cultural identity. Ben Santos’ wonderful writing is, in short, perhaps too Americanized in style—a style which carries stories of cultural loss and devastation. Gonzalez every now and then would mention how so many Filipino writers—Santos included—had given in to cultural despair, and one wonders to what degree being so adept at the “King’s English,” so to speak, is related to this despair, this sense of a lost Filipino cultural identity.

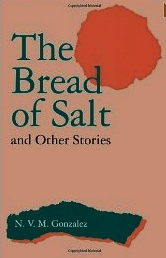

Gonzalez’s style, though awkward in many places compared to Bulosan’s, Santos’, and Hagedorn’s, nevertheless is beautiful and feels “more Filipino.” This is obviously so when he is writing about Filipino peasants in the cycle of harvest in the Philippines, for example, but also so when he writes about Filipinos in the United States. Take this passage chosen at random from the short story “The Tomato Game,” which has appeared in many places, including his story collection The Bread of Salt. “I saw Sopi in the mirror of my prejudices. He was thin but spry, and he affected rather successfully the groovy appearance of a professional, accepted well enough in the community and, at that, with deserved sympathy.” It’s the word “groovy” following the word “affected;” the way the “at that” breaks the sentence’s rhythm in not quite the right place. As much as this surely reflects his ear, when one looks at his work as a whole one realizes that it also reflects consciously a Filipino rhythm based in the cycles of planting and harvest, of landfall and sea-faring, colonized outsider longing for something like inside status, that clashes with the rhythm of a society he never will quite understand or be a part of. Or a language he feels the same way about. Gonzalez has said that adopting English, while it created a kind of larger cultural consciousness for Filipinos, also marked the downfall of their literary/cultural sensibilities.

Gonzalez’s style, though awkward in many places compared to Bulosan’s, Santos’, and Hagedorn’s, nevertheless is beautiful and feels “more Filipino.” This is obviously so when he is writing about Filipino peasants in the cycle of harvest in the Philippines, for example, but also so when he writes about Filipinos in the United States. Take this passage chosen at random from the short story “The Tomato Game,” which has appeared in many places, including his story collection The Bread of Salt. “I saw Sopi in the mirror of my prejudices. He was thin but spry, and he affected rather successfully the groovy appearance of a professional, accepted well enough in the community and, at that, with deserved sympathy.” It’s the word “groovy” following the word “affected;” the way the “at that” breaks the sentence’s rhythm in not quite the right place. As much as this surely reflects his ear, when one looks at his work as a whole one realizes that it also reflects consciously a Filipino rhythm based in the cycles of planting and harvest, of landfall and sea-faring, colonized outsider longing for something like inside status, that clashes with the rhythm of a society he never will quite understand or be a part of. Or a language he feels the same way about. Gonzalez has said that adopting English, while it created a kind of larger cultural consciousness for Filipinos, also marked the downfall of their literary/cultural sensibilities.

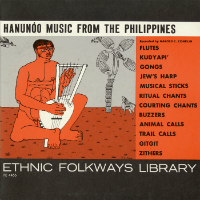

Yet for all this he was not a pessimistic artist. Though he never adopted what I have referred to as the “international style,” he saw the way there, and almost gave permission to other Filipino writers to conceive of themselves more broadly not as tied to a specific Filipino locale, but as being set loose in a new, international, globalized world. In his essay “Kalutang: A Filipino in the World,” his image of himself, and of what the Filipino artist could be, is of the tribal Hanunoo peasant walking through the forrest playing two sticks, the kalutang. “The song helps the soul know where the body is,” he writes. And the kalutang may take many forms—even, as it does at the essay’s close, a KLH portable player on which Gonzalez plays a tape of a Hanunoo playing the kalutang, because, as he says, “Who knows where I’ll be tomorrow.” The point is that the Filipino artist can be conceived as a Hanunoo, now wandering not a Filipino forrest but the world at large. “Perhaps,” says Gonzalez, “through his artistic effort the Filipino can contribute to the dialog of cultures now going on all over the world.”

Yet for all this he was not a pessimistic artist. Though he never adopted what I have referred to as the “international style,” he saw the way there, and almost gave permission to other Filipino writers to conceive of themselves more broadly not as tied to a specific Filipino locale, but as being set loose in a new, international, globalized world. In his essay “Kalutang: A Filipino in the World,” his image of himself, and of what the Filipino artist could be, is of the tribal Hanunoo peasant walking through the forrest playing two sticks, the kalutang. “The song helps the soul know where the body is,” he writes. And the kalutang may take many forms—even, as it does at the essay’s close, a KLH portable player on which Gonzalez plays a tape of a Hanunoo playing the kalutang, because, as he says, “Who knows where I’ll be tomorrow.” The point is that the Filipino artist can be conceived as a Hanunoo, now wandering not a Filipino forrest but the world at large. “Perhaps,” says Gonzalez, “through his artistic effort the Filipino can contribute to the dialog of cultures now going on all over the world.”

For this job having an “empty center” at the heart of one’s cultural identity may not be all that bad. As the deconstructionists have told us for 50 years, conceiving a stable center is folly anyway, an attempt to still the play of language and meaning, something which cannot really be done. As he often did, Gonzalez suggests ways to turn a perceived cultural liability into an asset. At this point we can suggest that not having an “authentic” Filipino style based on a stable cultural identity may not necessarily be something to worry that much about. Being protean, malleable, unafraid of a multitude of masks may be much more important. Thus the successful mastery of Hemingway’s stylistics, “standard” American story-telling rhythms, or even something like what appears to be a growing sense of an “international style” is not necessarily a sign of the inauthentic. As Mira Nair and others have told us for many years, “authenticity” is itself a kind of racist trap. One needs two sticks to strike together musically, some kind of kalutang song to help the soul keep track of the body, but not to center it. Instead it merely provides a song against which we trace the many forms, many styles we will take on, and, as it turns out, the Filipino writer has been doing this probably longer than any other group of writers. It’s just that they were worrying about that “empty center” too much. They had not realized what an asset it was going to be in this new internationalized world of border crossings, cultural hybridity, and multiple global identities. It’s just that we had forgotten to pack our music sticks.

♦ Read PART 1. Go HERE for a list of all writings on the Philippines, including an article and video on the Filipino “Concert King and Queen” and the Filipino affinity for Western music. And go here for a longer article focused on N.V.M. Gonzalez.

♦ Go to World Writers, the Teaching Diversity main page, or the “Third World” lead post.