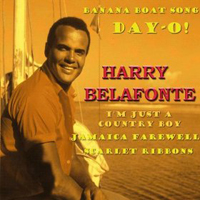

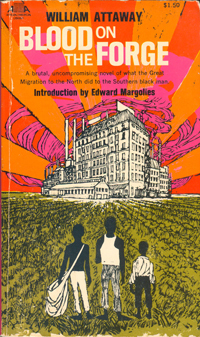

One of the most versatile black writers in American history, William Attaway wrote poems, stories, plays, music, and scripts for radio, television, and film. With the appearance of his first novel Let Me Breathe Thunder in 1939, and especially Blood on the Forge in 1941, reviewers were predicting a great future as a novelist for William Attaway—one on the level, perhaps, of Richard Wright. Like Wright, Attaway himself took part in the mass migration from the South—again, like Wright, from Mississippi to Chicago, where the two actually met and became friends when they worked together with the Federal Writer’s Project. Robert A. Bone called Blood on the Forge “by far the most perceptive novel of the Great Migration,” but it was to be Attaway’s last novel. Perhaps because of poor sales, Attaway turned instead to more lucrative screen and music writing, and would probably be best known today as the co-writer (with Irvin Burgie) of Harry Belafonte’s big 1950’s hit “The Banana Boat Song (Day-O-Day-O).” Attaway also wrote about and collected music with books like Calypso Songbook and Hear America Sing and was the first African American to write scripts regularly for film and television, producing work for programs like Wide Wide World and The Colgate Hour.

One of the most versatile black writers in American history, William Attaway wrote poems, stories, plays, music, and scripts for radio, television, and film. With the appearance of his first novel Let Me Breathe Thunder in 1939, and especially Blood on the Forge in 1941, reviewers were predicting a great future as a novelist for William Attaway—one on the level, perhaps, of Richard Wright. Like Wright, Attaway himself took part in the mass migration from the South—again, like Wright, from Mississippi to Chicago, where the two actually met and became friends when they worked together with the Federal Writer’s Project. Robert A. Bone called Blood on the Forge “by far the most perceptive novel of the Great Migration,” but it was to be Attaway’s last novel. Perhaps because of poor sales, Attaway turned instead to more lucrative screen and music writing, and would probably be best known today as the co-writer (with Irvin Burgie) of Harry Belafonte’s big 1950’s hit “The Banana Boat Song (Day-O-Day-O).” Attaway also wrote about and collected music with books like Calypso Songbook and Hear America Sing and was the first African American to write scripts regularly for film and television, producing work for programs like Wide Wide World and The Colgate Hour.

Like Belafonte, Attaway was deeply involved in the Civil Right’s Movement, marching with Martin Luther King, Jr., who called him “a fellow freedom fighter.” And one notes that “The Banana Boat Song,” not far beneath its seeming Calypso lightness, portrays workers struggling for a living. But Attaway’s Civil Rights participation in the states was cut short when he moved with his wife and children to Barbados in the early 60’s. They stayed for eleven years. His wife Frances was white. The racial turmoil following their marriage included death threats. It would be 1967 until the famous Arthur Loving case in Virginia finally struck down the last anti-miscegenation law in the country, but it would be two and a half more decades before more of the general American public approved of interracial relationships than disapproved. Attaway, dying in L.A. in 1986, would not live to see that turn.

Like Belafonte, Attaway was deeply involved in the Civil Right’s Movement, marching with Martin Luther King, Jr., who called him “a fellow freedom fighter.” And one notes that “The Banana Boat Song,” not far beneath its seeming Calypso lightness, portrays workers struggling for a living. But Attaway’s Civil Rights participation in the states was cut short when he moved with his wife and children to Barbados in the early 60’s. They stayed for eleven years. His wife Frances was white. The racial turmoil following their marriage included death threats. It would be 1967 until the famous Arthur Loving case in Virginia finally struck down the last anti-miscegenation law in the country, but it would be two and a half more decades before more of the general American public approved of interracial relationships than disapproved. Attaway, dying in L.A. in 1986, would not live to see that turn.

Though his work gained much critical praise, literary luminaries like Ralph Ellison and Addison Gayle found fault with Blood on the Forge for its pessimism and incomplete handling of the implications of black violence. They agreed, however, on the novel’s impressive style and ambition, and it remains perhaps his greatest literary achievement. The book tells the story of the three Moss brothers—Melody, Chinatown, and Big Mat. Several critics (Ellison chief among them) saw them as three sides of black consciousness: the artistic, the pagan, and the religious—though Big Mat’s broiling anger towards whites marked him as similar to Wright’s Bigger Thomas. Leaving the South and the land, they come to an ill-fated life of work in a Northern steel mill. In my book Black Writing from Chicago, I included a passage from Blood on the Forge describing their first nights in town. It is notable in part for its portrayal of ethnic violence against blacks, whom the steel mill owners would bring in every time there was any strike talk. Some of those ethnicities had not even attained “whiteness” yet themselves, but—in an old, historic, and tragic American process—their opposition to blacks would become one of the steps towards that assimilation into mainstream life.

Though his work gained much critical praise, literary luminaries like Ralph Ellison and Addison Gayle found fault with Blood on the Forge for its pessimism and incomplete handling of the implications of black violence. They agreed, however, on the novel’s impressive style and ambition, and it remains perhaps his greatest literary achievement. The book tells the story of the three Moss brothers—Melody, Chinatown, and Big Mat. Several critics (Ellison chief among them) saw them as three sides of black consciousness: the artistic, the pagan, and the religious—though Big Mat’s broiling anger towards whites marked him as similar to Wright’s Bigger Thomas. Leaving the South and the land, they come to an ill-fated life of work in a Northern steel mill. In my book Black Writing from Chicago, I included a passage from Blood on the Forge describing their first nights in town. It is notable in part for its portrayal of ethnic violence against blacks, whom the steel mill owners would bring in every time there was any strike talk. Some of those ethnicities had not even attained “whiteness” yet themselves, but—in an old, historic, and tragic American process—their opposition to blacks would become one of the steps towards that assimilation into mainstream life.

- Go to a complete list of Black Writers on this site.

- Go to the Teaching Diversity main page.

- Read my essay for more on the history of miscegenation.