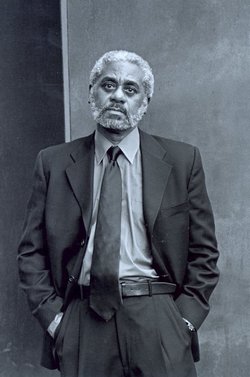

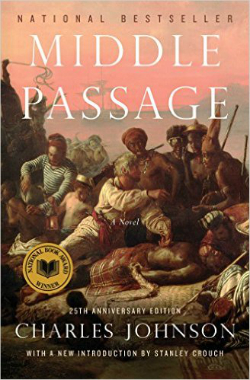

Born in Evanston, Illinois, in 1948, Charles Johnson’s first books were collections of cartoons—Black Humor in 1970, and Half-Past Nation Time in 1972. He also writes screenplays. Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1986) is a collection of stories, and his highly regarded novels include Faith and the Good Thing (1974), Oxherding Tale (1982), and Middle Passage (1990), a brilliant portrayal of the sea voyages which brought slaves to the Americas. It won the National Book Award, and in 1998 Johnson received a MacArthur Fellowship. After graduating from Southern Illinois University, Johnson did Ph.D. work in philosophy at SUNY-Stony Brook. His style—which combines folk elements, a sure ear for the vernacular, and an exploration of Black history—is closely related to the neo-realism of Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, though Johnson has stirred controversy by strongly urging Black writers to move beyond these writers. For Johnson a large part of what he advocates has to do with a more free-wheeling mixing of genres, time frames, and histories, and especially with his philosophical bent. “I am committed,” Johnson has said, “to the development of what one might call a genuinely systematic philosophical black American literature, a body of work that explores classical problems and metaphysical questions against the background of black American life.” Besides phenomenology a la Husserl, Johnson is also a devotee of Asian philosophy and the martial arts, and in some of his work—the story “China,” for example, from Sorcerer’s Apprentice—Johnson can be seen, as he says, “attempting to interface Eastern and Western philosophical traditions, always with the hope that some new perception of experience—especially ‘black experience’—will emerge….”

Born in Evanston, Illinois, in 1948, Charles Johnson’s first books were collections of cartoons—Black Humor in 1970, and Half-Past Nation Time in 1972. He also writes screenplays. Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1986) is a collection of stories, and his highly regarded novels include Faith and the Good Thing (1974), Oxherding Tale (1982), and Middle Passage (1990), a brilliant portrayal of the sea voyages which brought slaves to the Americas. It won the National Book Award, and in 1998 Johnson received a MacArthur Fellowship. After graduating from Southern Illinois University, Johnson did Ph.D. work in philosophy at SUNY-Stony Brook. His style—which combines folk elements, a sure ear for the vernacular, and an exploration of Black history—is closely related to the neo-realism of Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, though Johnson has stirred controversy by strongly urging Black writers to move beyond these writers. For Johnson a large part of what he advocates has to do with a more free-wheeling mixing of genres, time frames, and histories, and especially with his philosophical bent. “I am committed,” Johnson has said, “to the development of what one might call a genuinely systematic philosophical black American literature, a body of work that explores classical problems and metaphysical questions against the background of black American life.” Besides phenomenology a la Husserl, Johnson is also a devotee of Asian philosophy and the martial arts, and in some of his work—the story “China,” for example, from Sorcerer’s Apprentice—Johnson can be seen, as he says, “attempting to interface Eastern and Western philosophical traditions, always with the hope that some new perception of experience—especially ‘black experience’—will emerge….”

In my book Black Writing from Chicago, I included a story from Sorcerer’s Apprentice titled “The Education of Mingo,” a story with a perception of the black experience from another angle, both funny and horrifying. The story asks, What has the black man learned from observing white behavior? The white man in this case is named Moses Green, who  undertakes to “civilize” Mingo, a bondsman he has bought at auction. “Now Moses Green was not a man for doing things halfway,” writes Johnson. “Education, as he dimly understood it, was as serious as a heart attack. You had to have a model, a good Christian gentleman like Moses himself, to wash a Moor white in a single generation. As he taught Mingo farming and table etiquette, ciphering with knotted string, and how to cook ashcakes, Moses constantly revised himself. He tried not to cuss, although any mention of Martin Van Buren or Free-Soilers made his stomach chew itself; or sop cornbread in his coffee; or pick his nose at public market. Moses, policing all his gestures, standing the boy behind his eyes, even took to drinking gin from a paper sack so Mingo couldn’t see it. He felt, late at night when he looked down at Mingo snoring loudly on his corn-shuck mattress, now like a father; now like an artist fingering something fine and noble from a rude chump of foreign clay. It was like aiming a shotgun at the whole world through the African, blasting away all that Moses, according to his lights, tagged evil, and cultivating the good.” What Mingo learns, however, is not what Moses had hoped. He learns something deeper than Christian platitudes and table manners: he learns the relationship of whiteness and violence.

undertakes to “civilize” Mingo, a bondsman he has bought at auction. “Now Moses Green was not a man for doing things halfway,” writes Johnson. “Education, as he dimly understood it, was as serious as a heart attack. You had to have a model, a good Christian gentleman like Moses himself, to wash a Moor white in a single generation. As he taught Mingo farming and table etiquette, ciphering with knotted string, and how to cook ashcakes, Moses constantly revised himself. He tried not to cuss, although any mention of Martin Van Buren or Free-Soilers made his stomach chew itself; or sop cornbread in his coffee; or pick his nose at public market. Moses, policing all his gestures, standing the boy behind his eyes, even took to drinking gin from a paper sack so Mingo couldn’t see it. He felt, late at night when he looked down at Mingo snoring loudly on his corn-shuck mattress, now like a father; now like an artist fingering something fine and noble from a rude chump of foreign clay. It was like aiming a shotgun at the whole world through the African, blasting away all that Moses, according to his lights, tagged evil, and cultivating the good.” What Mingo learns, however, is not what Moses had hoped. He learns something deeper than Christian platitudes and table manners: he learns the relationship of whiteness and violence.

Many black writers—James Baldwin, James Alan McPherson, Haki Madhubuti—have marveled at how blacks have remained so human under the thumb and tutelage of white violence—Baldwin speculating particularly on how whites must have wondered at the depths of black superiority that allowed them to endure without striking back. And this is so even in the face of the largely black-on-black violence we now see gripping some Chicago neighborhoods, for example, a violence targeted in Spike Lee’s film Chi-raq, a name that speaks volumes and has engendered much controversy. There certainly is a “Chi-raq,” to go along with a Ferguson, a Baltimore, a Charleston—to name just a few recent examples from a history of white violence against blacks that reaches far, far back, nearly to the first white footsteps on the continent. Contemplating this, one does wonder how blacks managed not to “learn” so much violence, at least not to practice it against whites. Some have connected black-on-black, Chi-raqi violence to suppressed rage, a “rage of the disesteemed” Baldwin called it. “All too often,” Leon Litwack writes in Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow, “thoughts of revenge against whites found an outlet only in violence against blacks.”

The end of “The Education of Mingo” has Moses Green and Mingo fleeing an act of violence, the last lines of the story being: “‘Missouri,’ said the old man, not to Mingo but to the dusty floor of the buckboard, ‘if I don’t misremember, is off thataway somewheres in the west'”—a west where one day a town named Ferguson would be founded, just outside St. Louis.

♦ Go to a list of Black Writers on this site.

♦ Go to the Black Writing from Chicago page, where you can also BUY the book.