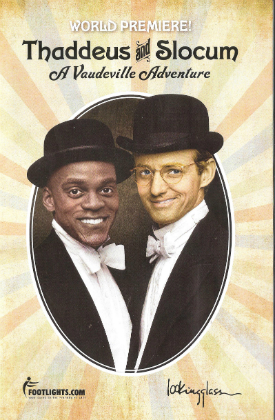

In his great essay “Junior and John Doe,” James Alan McPherson says, “There used to be the basic, if unspoken, assumption that identity in America is almost always a matter of improvisation, a matter of process…and that, given the provisional nature of American reality at almost any time, ‘black’ could in reality be ‘white,’ and ‘white’ could in reality be ‘black.'” I kept thinking of this as I watched Chicago’s Lookingglass Theater world premiere production of Thaddeus and Slocum: A Vaudeville Adventure, written by ensemble member Kevin Douglas.

In his great essay “Junior and John Doe,” James Alan McPherson says, “There used to be the basic, if unspoken, assumption that identity in America is almost always a matter of improvisation, a matter of process…and that, given the provisional nature of American reality at almost any time, ‘black’ could in reality be ‘white,’ and ‘white’ could in reality be ‘black.'” I kept thinking of this as I watched Chicago’s Lookingglass Theater world premiere production of Thaddeus and Slocum: A Vaudeville Adventure, written by ensemble member Kevin Douglas.

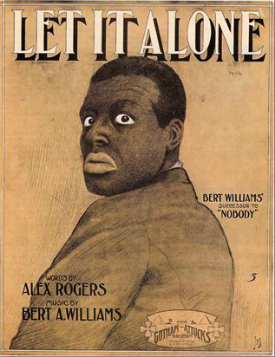

The play tells the story of two vaudevillians, one black (Thaddeus), one white (Slocum), who lived as brothers, schooled in the biz by Slocum’s Dad, an Irish-American. They’re not making it to the big houses for the obvious 1908 racist reasons, until Slocum has an idea. He’s been trying out an old minstrel staple, performing in blackface, and proposes that they appear together, both in blackface. Thaddeus hesitates, of course, though Slocum points out that one of the country’s biggest starts, Bert Williams, is a black man who performs in blackface. Thaddeus reluctantly agrees.

They go to one of Chicago’s biggest vaudeville houses and watch as one of the main stars, Isabelle, performs a lush, romantic song of the period. Everyone’s enchanted by this beautiful white woman, especially our two protagonists who’ve just agreed to hide a black identity under blackface. If they’re caught, they’re through. Then a series of slips between characters reveals that Isabelle has been hiding her own secret.  She’s passing. Though she certainly appears white, she would certainly be considered black if anyone knew her mixed parentage. For decades all it took was 1/32nd “black blood” to be classified as fully black, but for all these years the really dangerous person was the “octoroon,” someone 1/8th black, a combination which often assured white looks, but contained enough black that children might come out looking black.

She’s passing. Though she certainly appears white, she would certainly be considered black if anyone knew her mixed parentage. For decades all it took was 1/32nd “black blood” to be classified as fully black, but for all these years the really dangerous person was the “octoroon,” someone 1/8th black, a combination which often assured white looks, but contained enough black that children might come out looking black.

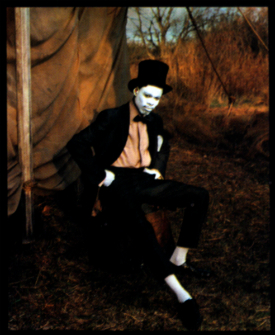

It’s an identity game—white in reality being black, black in reality being white, blackness hiding its reality under…blackness. Isabelle and Thaddeus, especially, have their careers—maybe even their literal lives—at stake and eventually fall in love. For me the play’s central scene is where the two sneak at night into the big Chicago theater where Thaddeus and Slocum originally saw Isabelle, and on whose stage they’ll finally appear the next night. Thaddeus and Isabelle start to dance, and I thought, We’ve been doing this black/white dance of intimacy, denial, and deception for such a long, long time.

I was at the play to be on a panel leading the audience in a discussion afterwards. I said that in the introduction to my book Black Writing from Chicago I had written that all Americans were at least 1/3rd black no matter what they were. America’s culture, its dedication to human rights, its religious tone—all these and more have been overwhelmingly influenced by blackness. This mixture of black and white virtually defines what the United States is. We are inextricably mixed by blood as well but work hard to forget this. One audience member caught this tension well when she said what most struck her about the play was how close black and white were in private, but how hard they had to deny this in public. U.S. demographics probably indicate an inexorable movement towards increasing diversity, but given our most recent string of racial explosions—the police killings of young black men in Baton Rouge, St. Paul, and other places, and the retaliatory killings of police—I asked the audience whether they thought we were at a tipping point where, on the one hand, racism was going to be lessening or, on the other hand, increasing. Does the rhetoric and ideology of fear and xenophobia running wild in the 2016 Presidential campaign indicate a turn away from diversity or “just” the last gasp of an old order founded on white supremacy? Most agreed we were at a tipping point, but couldn’t quite figure out what where we were leaning. For the “turn-away-from” side, Congressman Steve King’s remarks at the 2016 RNC are particularly symbolic, while I’ve found Chris Rock’s thought about the “last gasp” both quirky and persuasive.

As for Thaddeus and Slocum itself, it being a premiere there’s still work to do on the script, of course. Others have commented on its rushed, slightly unsatisfying ending, for example, and one critic’s comparison of it to Hamilton reminds us that sometimes it’s just unfortunate timing to first appear in the same year an international, supernova sensation does. I myself did feel distracted at times by scenes and vaudeville acts which seemed to go too long, but I came away admiring how well Thaddeus and Slocum helps us feel how harmful hiding or denying the inextricable mixing of black and white is. I have written many times that Americans would rather talk about anything—anything—but race and hope the talking space our after-play discussion provided could become more the norm. Talk after racially charged explosions of violence often leads to damaging discussions. Art can provide spaces both intense enough and safe enough to begin facing how entwined black and white are and how denying this, as Steve King so spectacularly did, has only nourished and continues to nourish racism.

♦ Go to a list of Black Writers written about on this site.

♦ Go to the Teaching Diversity main page.

Wow, good piece. I thought Slocum was a Jew at first. But meh, Irish works too for that time period. Gonna check out more, as one of those main characters share my race AND name!