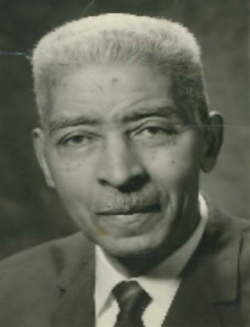

Because he had to work to help support his family and could not attend school regularly, John Lee Tilley (1898-1971) did not graduate high school until he was 23. He went to Shaw University for a B.A., and then—as important as land was to free Blacks—John Tilley’s parents mortgaged their tobacco farm so their son could come to study at the University of Chicago. While a student he was an active member of the Washington Intercollegiate Club, and one of his two books—A Brief History of the Negro in Chicago, 1779-1933—was used in the important student publication The Intercollegiate Wonder Book. He earned a masters degree and completed Ph.D. course work, but before he could complete his dissertation, Shaw persuaded him to return. It awarded him the Doctor of Divinity, and he stayed from 1927 to 1944, becoming its acting president during the Depression and the first dean of its School of Religion.

Because he had to work to help support his family and could not attend school regularly, John Lee Tilley (1898-1971) did not graduate high school until he was 23. He went to Shaw University for a B.A., and then—as important as land was to free Blacks—John Tilley’s parents mortgaged their tobacco farm so their son could come to study at the University of Chicago. While a student he was an active member of the Washington Intercollegiate Club, and one of his two books—A Brief History of the Negro in Chicago, 1779-1933—was used in the important student publication The Intercollegiate Wonder Book. He earned a masters degree and completed Ph.D. course work, but before he could complete his dissertation, Shaw persuaded him to return. It awarded him the Doctor of Divinity, and he stayed from 1927 to 1944, becoming its acting president during the Depression and the first dean of its School of Religion.

In 1927, just before leaving Chicago, Tilley sat at the base of Lorado Taft’s monumental “Fountain of Time” sculpture at the entrance to the Midway and penned the poem “When Day Is Done,” which I included in my book Black Writing from Chicago, along with excerpts from the aforementioned Intercollegiate Wonder Book. Imbued with themes and an articulate melancholy not uncommon in the Black poetry of the time, it represents a midpoint between the optimism of the Intercollegiate crowd, which championed Black accomplishment and the New Negro, and the stark pessimism of poet Fenton Johnson.

After his 17 year stint at Shaw, he went on to serve as president of Florida Normal and Industrial College from 1944 to 1949, and then went to Baltimore as dean of the Maryland Baptist Center and School of Religion, as well as becoming pastor of the Metropolitan Baptist Church. In 1957 he became director for the NAACP’s Register and Vote campaign in Baltimore, adding 35,000 voters in one year. This led Martin Luther King, Jr. to call him to be the first national executive secretary of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in early 1958. By April 1959, however, King had asked for his resignation. The SCLC felt it needed more from him, but Tilley felt—and he reminded King of this—that he could work for the SCLC only part time because his church and his city still also needed him. In Baltimore he was a dean, and a pastor, and a mainstay of the NAACP.

His poem “When the Day Is Done” is prescient about the costs of all the accomplishments ahead, and one also senses a backward glance at the sacrifices he had already made that put off his high school graduation until his early 20’s. As shadows fall at day’s end, the poem’s speaker reflects on how these shadows dim the bright day. He juxtaposes “Bright hope and all that seems to be worthwhile” with “The rose so fresh that soon must fade away,” as do pleasures: “They thrill us through but pass forever on, / And as they pass to us they seem to say, / ‘To thrill and pain and leave is why we were born.’” At the end of life, he only asks, “May I but have the joy that I have won / For some sad hearts real joys that will abide.” The poem reflects the weariness of one who felt the responsibility of carrying so many burdens. His daughter Glennette Tilley Turner lives in the Chicago area and has written books and given many talks on Illinois’ Underground Railroad.

♦ Go to a list of Black Writers on this site, to the main page for Black Writing from Chicago, and to the Teaching Diversity main page.