May 2020 Update:  Another “I-Can’t-Breathe” incident. I could not watch the video of the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 26, 2020. But I heard it while my wife described to me what she was seeing: a police man with his knee on the neck of an already-subdued black man. It was on YouTube. A few will see these cops as heroes, but just as disturbing will be all those familiar gasps of disbelief: “How can this be happening in 2020?!” —while virtually nothing else will be done. The article below was originally published on February 11, 2015, and revisited on July 13, 2016. I could have revisited it many more times in between, and there will doubtless be more “opportunities” to do so for the conceivable future…

Another “I-Can’t-Breathe” incident. I could not watch the video of the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 26, 2020. But I heard it while my wife described to me what she was seeing: a police man with his knee on the neck of an already-subdued black man. It was on YouTube. A few will see these cops as heroes, but just as disturbing will be all those familiar gasps of disbelief: “How can this be happening in 2020?!” —while virtually nothing else will be done. The article below was originally published on February 11, 2015, and revisited on July 13, 2016. I could have revisited it many more times in between, and there will doubtless be more “opportunities” to do so for the conceivable future…

____________________

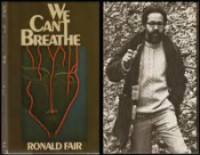

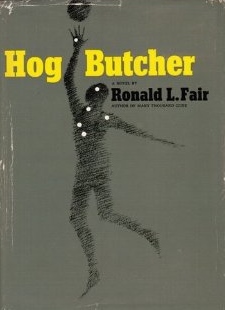

Many Thousands Gone, published in 1965, brought Ronald L. Fair (b. 1932) considerable critical acclaim, and that novel was quickly followed the next year by Hog Butcher. In 1970 Fair published two novellas as World of Nothing, which received the National Institute of Arts and Letters second-highest prize, and 1972 saw the publication of the autobiographical novel We Can’t Breathe. For several years, aided by several writing grants, Fair traveled abroad, pursuing a writing life of great ambition. In the early 70’s critic Shane Stevens called him “one of the two best black writers in the country.” Yet this promise somehow never came to full fruition. In 1977 he relocated to Finland, dedicating himself more to sculpture than writing. In December 1980 he became “born again,” thereafter identifying himself as a “Christian writer” and founding the International Orphans’ Assistance Association.

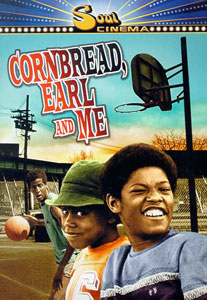

Perhaps his most successful book, the novel Hog Butcher revolves around the shooting by Chicago police of an innocent black basketball star, Corn Bread. This was the basis of the 1975 film Cornbread, Earl and Me, with a cast including Rosalind Cash and a very young Laurence Fishburne. Though some have commented on the novel’s humor and, in particular, on the energy and courage of the two adolescent protagonists through whom some of the action is seen, the novel is a sobering exploration of social class…and, of course, police violence. It’s a topic much in the news—again—with the 2014 deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Dontre Hamilton in Milwaukee, Eric Garner in Staten Island, who kept gasping, “I CAN’T BREATHE”…. Besides the many “non-suspicious” shootings by police and others of young black men, there have been at least 29 decidedly suspicious shootings since 2012—16 of them occurring after Trayvon Martin. As I revisit this article now, on July 13, 2016—just 17 months after its original posting—the tragedies in Baton Rogue, St. Paul, and Dallas continue to reverberate across the nation, though these usually just result in people being so surprised that racism is still with us.

Perhaps his most successful book, the novel Hog Butcher revolves around the shooting by Chicago police of an innocent black basketball star, Corn Bread. This was the basis of the 1975 film Cornbread, Earl and Me, with a cast including Rosalind Cash and a very young Laurence Fishburne. Though some have commented on the novel’s humor and, in particular, on the energy and courage of the two adolescent protagonists through whom some of the action is seen, the novel is a sobering exploration of social class…and, of course, police violence. It’s a topic much in the news—again—with the 2014 deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Dontre Hamilton in Milwaukee, Eric Garner in Staten Island, who kept gasping, “I CAN’T BREATHE”…. Besides the many “non-suspicious” shootings by police and others of young black men, there have been at least 29 decidedly suspicious shootings since 2012—16 of them occurring after Trayvon Martin. As I revisit this article now, on July 13, 2016—just 17 months after its original posting—the tragedies in Baton Rogue, St. Paul, and Dallas continue to reverberate across the nation, though these usually just result in people being so surprised that racism is still with us.

Rodney-King-like beatings continue as well, and, given Eric Garner’s fate, Fair’s title—We Can’t Breathe—echoes eerily across the nearly five decades since the novel’s publication. It’s almost too much to keep up with, and we are disheartened to see the pace of these incidents has not slowed.

I included two excerpts from Hog Butcher in my book Black Writing from Chicago, the first excerpt a surprising essay interlude appearing half-way through the book. It sets the novel’s particular action against a history of social class and the Great Migration of Blacks from the South in the early 20th Century. It excoriates the pretensions and weakness that, according to Fair, beset many of those early migrants and their children. “They came to Chicago forty, fifty years ago like a school of black minnows frantically dashing away from danger,” the excerpt begins. They then

I included two excerpts from Hog Butcher in my book Black Writing from Chicago, the first excerpt a surprising essay interlude appearing half-way through the book. It sets the novel’s particular action against a history of social class and the Great Migration of Blacks from the South in the early 20th Century. It excoriates the pretensions and weakness that, according to Fair, beset many of those early migrants and their children. “They came to Chicago forty, fifty years ago like a school of black minnows frantically dashing away from danger,” the excerpt begins. They then

“…shouldered their way in and mingled with the foreigners and fought the aliens for jobs, and won the jobs as they won the negative respect of the established citizens. They squeezed their way as close to the existing social structure as they were allowed to go, and then they settled back and prospered and raised children and taught their children not to fight, not to resist, but to accept their limited progress as the end of the evolutionary pattern. They grew weak and mellowed from their success, and their children never developed hearts or shoulders or minds, and were gutless.

“Their children refused to involve themselves with trivial things like politics or social improvements and pulled in the fences that surrounded their tiny ranch houses. Their children tightened the requirements for entrance into their sick social clubs. At first they only wanted light skin and straight hair. Then they added a college degree to the light skin and straight hair. Then they added a minimum salary. Then they added the possession of a Buick. Then they added the Cadillac. They had arrived; they had reached the top of their limited world and they were scared shitless.”

The second excerpt illustrates that “gutless” history by focusing on Larry Atkins, a Black Chicago police officer close enough to the killing to be a decisive factor in uncovering the truth that is being lost in a clumsy cover-up. Will Atkins rise to the challenge? That is the question that occupies much of the book’s second half. At first, Larry dreams of becoming a teacher, helping kids, uplifting the neighborhood, but he’s worn down by neighborhood crime, he’s shot, he’s knifed. He gives up. I end my excerpt with these words:

“He found himself wanting to be something other than a black man and finally succeeded in convincing himself that he had nothing in common with these people except color, which was purely an accident of birth…He would finish school and he would become a teacher, but not because he was dedicated, not any longer…He would take up teaching because he wanted to break all ties with that animalistic world, and becoming a professional man would make the break final. This would put him at the very pinnacle of his middle-class society, and he would never look back again.”

“He found himself wanting to be something other than a black man and finally succeeded in convincing himself that he had nothing in common with these people except color, which was purely an accident of birth…He would finish school and he would become a teacher, but not because he was dedicated, not any longer…He would take up teaching because he wanted to break all ties with that animalistic world, and becoming a professional man would make the break final. This would put him at the very pinnacle of his middle-class society, and he would never look back again.”

The subtitle of Black Writing from Chicago is “In the World, Not of It? You can read the book’s Introduction, paying particular attention to my idea that the controversy over how much Blacks should want to be part of “the World”—that is, a society which so violently and systematically shuts them out—boils down to attitudes about middle-classness (see below). It’s a way up and out, but at what price? (James Baldwin was obsessed with this price.) This argument, this complex dilemma, runs through my book like, as one critic put it, a “charged current.” The tragic run of shootings and beatings referred to above have had tens of thousands of precedents which were not caught on film or even live-streamed, as Philando Castile’s shooting was. The middle-classness that Ronald L. Fair indicts—a condition that besets both whites, obviously, and blacks—might be moved by our age’s overwhelming video evidence, plus the use of social media by #blacklivesmatter and others. There’s a slim chance it could move more and more of us to be less gutless in challenging “the World,” instead of just being surprised that it’s still so racist.

♦ Read Leanita McClain and Barack Obama on “Middle-Classness.”

♦ Read Haki Madhubuti on whether Black Men are “obsolete.”

♦ Go to a list of Black Writers written about on this site, and to the Teaching Diversity main page. And go to my newer series on Unpacking Racism.

Ron gave up trusting the folks who were supposed to ‘fix’ these problems. Probably best, but the US lost an important voice when he left.