This article is part of two continuing series on Chicago Writers, most of whom are contained in two of my Chicago books: Black Writing from Chicago, and, with David Starkey, Smokestacks and Skyscrapers. Go to complete lists of Chicago and Black writers in this series.

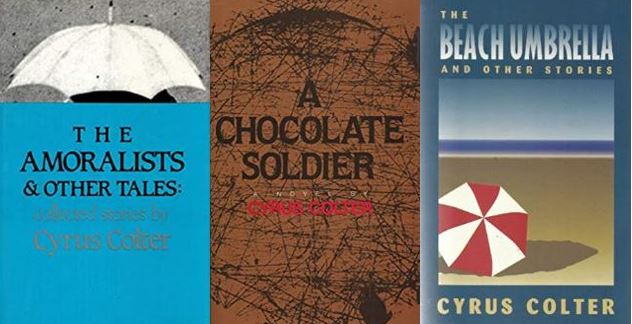

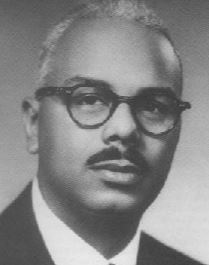

Born in Noblesville, Indiana, in 1910, Cyrus Colter (1910-2002) received his law degree from Chicago-Kent College of Law in 1940 and began a successful career in business and government as a lawyer and, from 1950 to 1973, as commissioner of the Illinois Commerce Commission. He was 60 when his first collection of stories, The Beach Umbrella (1970), won the University of Iowa’s School of Letters fiction prize. The success of his novels The River of Eros (1972) and The Hippodrome (1973) led to his appointment as the Chester D. Tripp Professor of Humanities at Northwestern University from 1973 to 1978. Night Studies (1979) won the 1980 Carl Sandburg fiction prize. In 1988, he published A Chocolate Soldier and his collected stories The Amoralist and Other Tales. In 1993, he published City of Light.

The stories in The Amoralist explore Black life, or the reaction to it, from the ghetto to the anxiety-ridden world of the Black middle class. In “The March,” the book’s most spectacular, outgoing story, a mother sees her 18-year-old son Archie off to the Army and an almost certain assignment to Vietnam, then returns home to deal with the indifference and bitterness of her second husband and the protests sweeping the neighborhood. Leaflets for an anti-war march read, in part: “Join the thousands of protestors who will MARCH! Then hear speeches about the cruel hoax of our NEGRO BOYS fighting and dying in Vietnam…Why are we sending NEGRO BOYS thousands of miles across the seato fight for so-called DEMOCRACY when these same boys never shared it right here at home?” Other stories are quieter and powerfully indirect, as in “Chance Meeting,” where an elderly house servant’s identity and seeming closeness to his former high society employer is undermined by chance, unwelcomed revelations.

The stories in The Amoralist explore Black life, or the reaction to it, from the ghetto to the anxiety-ridden world of the Black middle class. In “The March,” the book’s most spectacular, outgoing story, a mother sees her 18-year-old son Archie off to the Army and an almost certain assignment to Vietnam, then returns home to deal with the indifference and bitterness of her second husband and the protests sweeping the neighborhood. Leaflets for an anti-war march read, in part: “Join the thousands of protestors who will MARCH! Then hear speeches about the cruel hoax of our NEGRO BOYS fighting and dying in Vietnam…Why are we sending NEGRO BOYS thousands of miles across the seato fight for so-called DEMOCRACY when these same boys never shared it right here at home?” Other stories are quieter and powerfully indirect, as in “Chance Meeting,” where an elderly house servant’s identity and seeming closeness to his former high society employer is undermined by chance, unwelcomed revelations.

In Smokestacks and Skyscrapers, the Chicago anthology I edited with David Starkey, David chose “Beach Umbrella,” the famous story that launched Colter’s writing career. It explores one of Chicago literature’s most enduring themes, class consciousness, as we watch the main character, Elijah, juggle the reality of his blue-collar existence and the fantasy world he has created at the 31st Street Beach. He feels constant pressure from his wife Myrtle to find another job and make more money, but at the warehouse where he works he’s worked his way up from a freight handler to doing inventories and a little paperwork. He wears a tie to work, and, though the pay is low, speaks of it as a white-collar job. He thinks of moving on, but won’t risk it. What he does risk is borrowing $15 from his more enterprising son Randall to help him buy a beach umbrella. He’s fascinated by the variety of them at the beach, and the way they seem to attract people who have the most fun. In the end, though, his one day of attracting people seems hollow, and wondering how he’s going to pay his son back, he tries unsuccessfully to sell it.

In Black Writing from Chicago I chose the story “Overnight Trip,” one of Colter’s most quiet, interior stories. After Amos, the main character, gets a job as a linotype machine operator and marries Penny, he thinks he’s made it. “He breathed easier, confiding to himself that he was finally ‘out of the woods.’ But now he realized you never were…His mother, now long dead, used to say to him, ‘Keep agoin’ fou-werd, Amos, and look to Jesus an’ everything will come out all right.’ It was a mild shock to regard this as possibly untrue.” He wonders “what it was about life that made it so risky,” why trouble seems to be always around the corner. This is especially true about his life with Penny. She wants children, but because he thinks of her as a child needing his constant protection against life’s risks, their love making is infrequent and awkward. He senses, rightfully, a growing distance between them, which only elevates his feeling of riskiness. Everything seems absolutely upended when her friend Bobbie invites her for an overnight trip to St. Louis. Though she demurs to Amos, she’s obviously excited to go. The story builds so quietly, so deep inside Amos’ mind, that the last line often strikes me as one of the most powerful quiet lines in literature and a signal of the enduring power of Colter’s writing: “He knew she’d return tomorrow night, but that really she was gone.”

In Black Writing from Chicago I chose the story “Overnight Trip,” one of Colter’s most quiet, interior stories. After Amos, the main character, gets a job as a linotype machine operator and marries Penny, he thinks he’s made it. “He breathed easier, confiding to himself that he was finally ‘out of the woods.’ But now he realized you never were…His mother, now long dead, used to say to him, ‘Keep agoin’ fou-werd, Amos, and look to Jesus an’ everything will come out all right.’ It was a mild shock to regard this as possibly untrue.” He wonders “what it was about life that made it so risky,” why trouble seems to be always around the corner. This is especially true about his life with Penny. She wants children, but because he thinks of her as a child needing his constant protection against life’s risks, their love making is infrequent and awkward. He senses, rightfully, a growing distance between them, which only elevates his feeling of riskiness. Everything seems absolutely upended when her friend Bobbie invites her for an overnight trip to St. Louis. Though she demurs to Amos, she’s obviously excited to go. The story builds so quietly, so deep inside Amos’ mind, that the last line often strikes me as one of the most powerful quiet lines in literature and a signal of the enduring power of Colter’s writing: “He knew she’d return tomorrow night, but that really she was gone.”