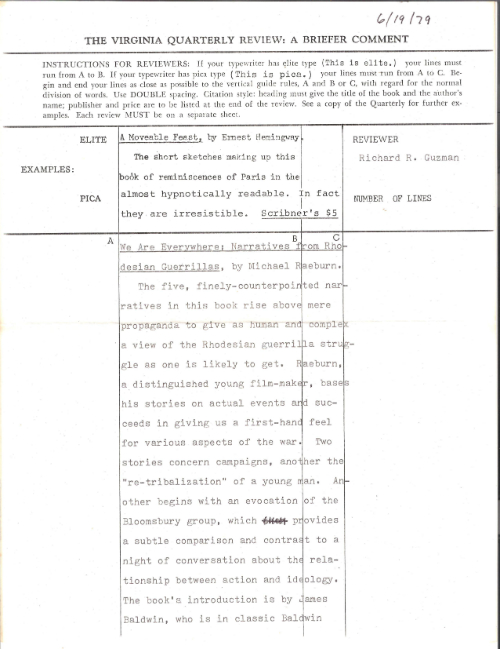

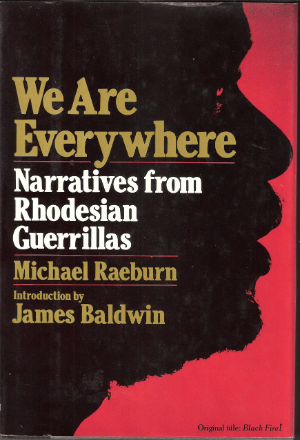

Above is a template for brief reviews used by the Virginia Quarterly Review in the old days, this one dated 6/19/79, when I, in response to a review copy of a book the VQR sent me, turned in this small note on Michael Raeburn’s We Are Everywhere: Narratives from Rhodesian Guerillas. James Baldwin wrote the Introduction, and the few words I quote from it—I say he’s in “classic Balwin form”—ring perhaps louder today than when I latched on to the words in 1979. The template says if you’re using elite type, type your review between vertical lines A and B; if using pica, type between lines A and C. Here’s the short note/review I wrote between A and C:

“The five, finely-counterpointed narratives in this book rise above mere propaganda to give as human and complex a view of the Rhodesian guerilla struggle as one is likely to get. Raeburn, a distinguished young film-maker, bases his stories on actual events and succeeds in giving us a first-hand feel for various aspects of the war. Two stories concern campaigns, another the ‘re-tribalization’ of a young man. Another begins with an evocation of the Bloomsbury group, which provides a subtle comparison and contrast to a night of conversation about the relationship between action and ideology. The book’s introduction is by James Baldwin, who is in classic Baldwin form. ‘Freedom for the black man,’ he says, ‘…will bring to the white man a joy and freedom he does not, now, dare to imagine.’

“Rhodesia—Zimbabwe today—has continued being, as the jacket blurb says, ‘one of the political tinder boxes of Africa,’ and it’s just gone through what we hope will usher in a joy and freedom it has long not dared to imagine. As the Financial Times reported on November 24, 2017, ‘Emmerson Mnangagwa committed to holding democratic elections next year as he was sworn in as president of Zimbabwe on Friday at a ceremony that was the culmination of an extraordinary 10 days that ended Robert Mugabe’s 37-year rule.’ Mnangagwa is an old Mugabe ally, so we’ll see.”

“Rhodesia—Zimbabwe today—has continued being, as the jacket blurb says, ‘one of the political tinder boxes of Africa,’ and it’s just gone through what we hope will usher in a joy and freedom it has long not dared to imagine. As the Financial Times reported on November 24, 2017, ‘Emmerson Mnangagwa committed to holding democratic elections next year as he was sworn in as president of Zimbabwe on Friday at a ceremony that was the culmination of an extraordinary 10 days that ended Robert Mugabe’s 37-year rule.’ Mnangagwa is an old Mugabe ally, so we’ll see.”

What I quoted from Baldwin rings especially true at this moment in American history decades after he wrote it. So many see this time as a turning point, a water-shed moment—at least they hope that’s what it is—led by the extraordinary backlash against sexual harassment and assault symbolized by #MeToo and #TimesUp. It’s a riskier, much less clear proposition to suggest that the white backlash that has spawned Donald Trump’s election and the resurgence of white power may be the beginning of the end of White Supremacy, too. (Chris Rock expressed a similar thought I commented on in “Chris Rock: Racism Almost Over?“) What men who want to preserve old-boy privilege, and whites who want to maintain their privilege and supremacy do not realize is, to paraphrase Baldwin, that freedom for women and people of color will bring to men and white people a joy and freedom they do not, now, dare to imagine. It takes so much energy and so much denial (always a dangerous thing) to maintain such privilege, to remain on top by pushing others down, to imagine such a lofty view of yourself—a view which always detaches you not only from the humanity of others, but your own humanity as well. “We are everywhere.” I can imagine that as one of the new slogans of this era when we finally realize—as we really have not for centuries of time—that women and people of color really are everywhere, and have always been.

♦ Go to All Things Baldwin for more on this site about James Baldwin, and go to the Teaching Diversity main page, and the Reviews and Commentary main page. In my sermon “Pentecost Means No Supremacies,” preached decades later, I use many of the same ideas I touched on in this short review.

We Are Everywhere

Above is a template for brief reviews used by the Virginia Quarterly Review in the old days, this one dated 6/19/79, when I, in response to a review copy of a book the VQR sent me, turned in this small note on Michael Raeburn’s We Are Everywhere: Narratives from Rhodesian Guerillas. James Baldwin wrote the Introduction, and the few words I quote from it—I say he’s in “classic Balwin form”—ring perhaps louder today than when I latched on to the words in 1979. The template says if you’re using elite type, type your review between vertical lines A and B; if using pica, type between lines A and C. Here’s the short note/review I wrote between A and C:

“The five, finely-counterpointed narratives in this book rise above mere propaganda to give as human and complex a view of the Rhodesian guerilla struggle as one is likely to get. Raeburn, a distinguished young film-maker, bases his stories on actual events and succeeds in giving us a first-hand feel for various aspects of the war. Two stories concern campaigns, another the ‘re-tribalization’ of a young man. Another begins with an evocation of the Bloomsbury group, which provides a subtle comparison and contrast to a night of conversation about the relationship between action and ideology. The book’s introduction is by James Baldwin, who is in classic Baldwin form. ‘Freedom for the black man,’ he says, ‘…will bring to the white man a joy and freedom he does not, now, dare to imagine.’

What I quoted from Baldwin rings especially true at this moment in American history decades after he wrote it. So many see this time as a turning point, a water-shed moment—at least they hope that’s what it is—led by the extraordinary backlash against sexual harassment and assault symbolized by #MeToo and #TimesUp. It’s a riskier, much less clear proposition to suggest that the white backlash that has spawned Donald Trump’s election and the resurgence of white power may be the beginning of the end of White Supremacy, too. (Chris Rock expressed a similar thought I commented on in “Chris Rock: Racism Almost Over?“) What men who want to preserve old-boy privilege, and whites who want to maintain their privilege and supremacy do not realize is, to paraphrase Baldwin, that freedom for women and people of color will bring to men and white people a joy and freedom they do not, now, dare to imagine. It takes so much energy and so much denial (always a dangerous thing) to maintain such privilege, to remain on top by pushing others down, to imagine such a lofty view of yourself—a view which always detaches you not only from the humanity of others, but your own humanity as well. “We are everywhere.” I can imagine that as one of the new slogans of this era when we finally realize—as we really have not for centuries of time—that women and people of color really are everywhere, and have always been.

♦ Go to All Things Baldwin for more on this site about James Baldwin, and go to the Teaching Diversity main page, and the Reviews and Commentary main page. In my sermon “Pentecost Means No Supremacies,” preached decades later, I use many of the same ideas I touched on in this short review.